ACEPHALE

ACEPHALE by David Medalla

When I saw the image of a headless man on the flyer of the multi-media exhibition ‘WHITE SNUFF’ which Adam Nankervis is curating at Ackerkelle in Berlin, I remembered a number of things.

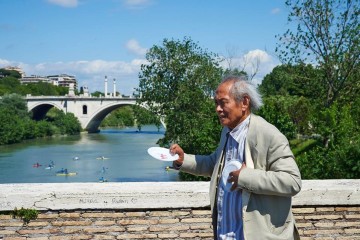

Firstly I remembered the time when Adam and I were in the centre of Rome in 2005.

While waiting for a bus to take us to the home of Adam’s friends Filippo Ceccarelli and Elena Polidori at Trastevere, we wandered into a church whose inner facade was covered with fragments of ancient marble sculpture like a large 3-dimensional collage in stone. We entered the church and saw, in a side chapel, a glass altar in which was stored the decapitated head of St. John the Baptist. There was no explanation of how the head of John the Baptist got there. From the palace of Herod Antipas in Judea to the side chapel in Rome is a long journey by any standard, possible only by means of a miraculous route through space and time.

The head of John the Baptist was the prize Salomé demanded from King Herod after she performed her Dance of the Seven Veils. In the 19th century writers and artists were obsessed by the story of Salomé and John the Baptist. The interest hovered between necrophilia and destructive eroticism.

Gustave Moreau depicted Salomé in jewel-like encrustations of paint. Maud Allan was celebrated for her Dance of the Seven Veils.

Stephane Mallarmé and Oscar Wilde were two writers who wrote about Salomé. Mallarmé’s monologue expressed in exquisite symbolist poetry the frustration and the erotic longing Salomé felt for the wild saint who baptised Jesus Christ (the Messiah) in the river Jordan. The scene of that baptism, as depicted in Piero della Francesca’s painting (now in the National Gallery in London), was the inspiration for a performance entitled ‘Four Aces’ which I gave (with the participation of twelve handsome young men) at the Swiss Institute in New York City, curated by Mathieu Copeland for ‘Performa 7′ in 2007.

Oscar Wilde’s ‘Salomé’ was transformed into a great opera by Richard Strauss.

Of the many depictions of the decapitated John the Baptist the most powerful is the painting by Caravaggio.

After seeing the head of St. John the Baptist I remembered the first (and only) time I saw a severed head. It was a shrunken head on a wooden pike stuck into the ground on a promontory (the boundary between the Ifugao and Igorot tribes) above the magnificent rice terraces of the Mountain Province of the Philippines. That was in 1951, probably the last time when the mountain tribes of the Philippines practised head-hunting as part of their tribal rituals and wars. I was ten years old, a student from the lowlands, at St. Mary’s School, a school ran by Episcopalian missionaries, in the town of Sagada near Bontoc. The mountain tribes of Luzon island subsequently converted into oppositing kinds of Christianity: Roman Catholicism, preached mainly by Belgian fathers, and different branches of Protestantism, preached by various sects, mainly American in origins. The Episcopalians who ran St. Mary’s School in Sagada came from New England.

When I first arrived in Paris in the spring of 1960, I visited the Cathedral of Notre Dame. I was surprised to find one of the sculptures at the entrance to the cathedral was a headless man who carried his had in his hand. I found out later that the headless man was Saint Denis, one of the two patron saints of Paris. The other was Saint Genevieve. I thought how strange: to be walking around, carriying one’s head in one’s hand. Chopping the heads of kings and queens and of criminals has long been in the DNA of the French.

A few years later my friend Christian Ledoux told me that his friend Philipp Garrell has made a film entitled ‘Acephale’ (‘Headless’). I have not yet seen the film, which has long been a part of the classics of French underground cinema of the 60s. I will ask Hermine Demoriane (who is also a friend of Philipp Garrell) to tell me what ‘Acephale’ is about.

Perhaps she can help me find a DVD copy of the film.

Hermine Demoriane runs the Chateau de Sacy in Picardie, France. Adam Nankervis will become an artist in residence there in the summer of this year 2010. I wonder if Adam will carry some remnant of the “White Snuff” show he is curating in Berlin to Chateau de Sacy in France. Or will the headless naked man on the flyer of the Berlin show accompany Adam to France. I wonder. Dans le monde d’art et de la poesie, toute est possible.

David Medalla – director of London Biennale

No Comment