STAGING ACTION FOCUSES ON THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN PHOTOGRAPHY AND PERFORMANCE OVER THE LAST 50 YEARS – MOMA | NY

Staging Action: Performance in Photography Since 1960

January 28–May 9, 2011

The Robert and Joyce Menschel Photography Gallery, third floor

The Museum of Modern Art, 11 West 53rd Street, New York, NY

www.moma.org

NEW YORK, December 13, 2010—Focusing on a wide range of images of performances that were expressly made for the artist’s camera, Staging Action: Performance in Photography Since 1960 draws together approximately 50 works from the Museum’s collection, and is on view from January 28 to May 9, 2011. Though performances are often intended to be experienced live, in real time, with photography playing an ancillary function in recording them, these works function as independent, expressive pictures, often staged in the absence of a public audience. At the center of these pictures is a performer (often the artist), posing or enacting an action conceived for the photographic lens. Among the works on view, approximately half are recent acquisitions by MoMA, including pieces by Laurel Nakadate, Rong Rong, Ai Weiwei, Huang Yan, and La Monte Young. Staging Action is organized by Roxana Marcoci, Curator, and Eva Respini, Associate Curator, Department of Photography, The Museum of Modern Art.

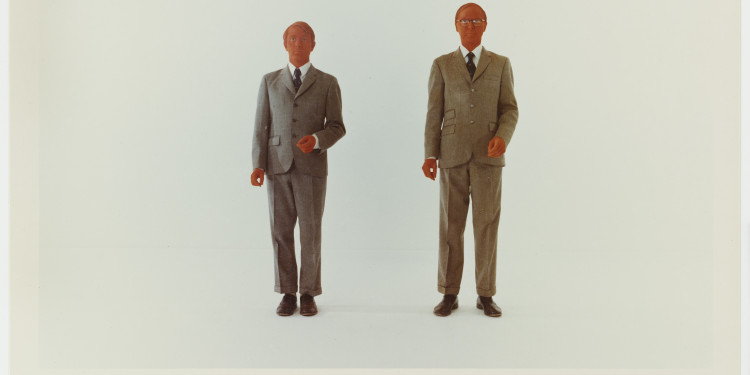

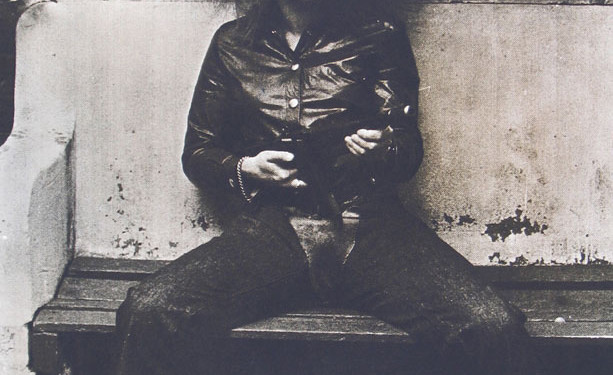

Beginning with Fluxus artists in the 1960s, Staging Action includes the work of George Maciunas, an artist who engaged the production of the self as positional rather than fixed and often played with transvestism. According to personal reminiscences of the American poet Emmett Williams, a friend, Maciunas’s closets were full of prom dresses that he scavenged from the Salvation Army. In his 1966 cross-dressing striptease, George Maciunas Performing for Self-Exposing Camera, New York, he reinforced the active construction of identity through gender indeterminacy. The participation of the camera as accomplice to the artist’s actions was also a constant theme in Vito Acconci’s work of the early 1970s. In Conversions I: Light, Reflections, Self-Control (1970-71), Acconci tried to feminize his male body by plucking hair from his chest and navel area, pushing his pectorals together to mimic breasts, and hiding his genitals between his legs. Performances that explored gender play were soon embraced by other artists. A few years later, Richard Prince and Cindy Sherman collaborated on a photo shoot in which they sported identical suits and red-haired wigs, each playing androgynous double to the other.

Staging Action continues with artists who experimented with the camera to test the physical and psychological limits of the body. Reacting against the post–World War II repressive sexual and political atmosphere of Austrian society, the group known as the Vienna Actionists—including Günter Brus, Otto Muehl, Herman Nitsch, and Rudolf Schwarzkogler—staged highly provocative actions that were mostly ritualistic, incorporating elements such as wine and animal blood from Dionysian rites and Christian ceremonies in an attempt to free human instincts that had been repressed by society. In the early 1990s, numerous artists living in Beijing’s East Village artist community actively engaged in endurance-based performances. On view is East Village, Beijing No. 22 (1994) by Rong Rong, an iconic picture of the now seminal performance known as 12 Square Meters, which takes its title from the size of the public urinal where the action took place. The artist Zhang Huan covered himself in fish guts and honey and sat motionless for an hour in the heat of a summer day as flies gathered on his body, while the photographer Rong Rong captured the gritty performance.

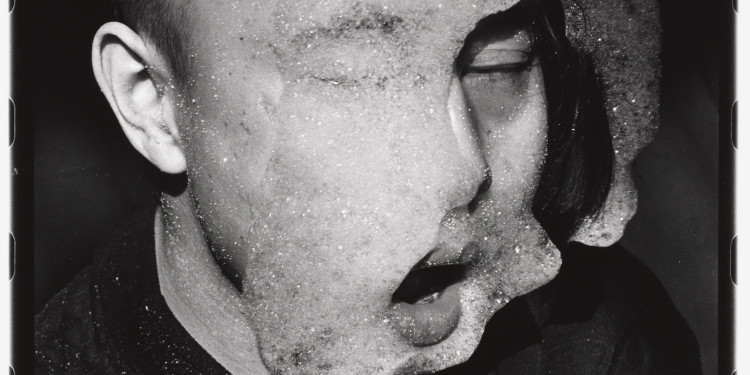

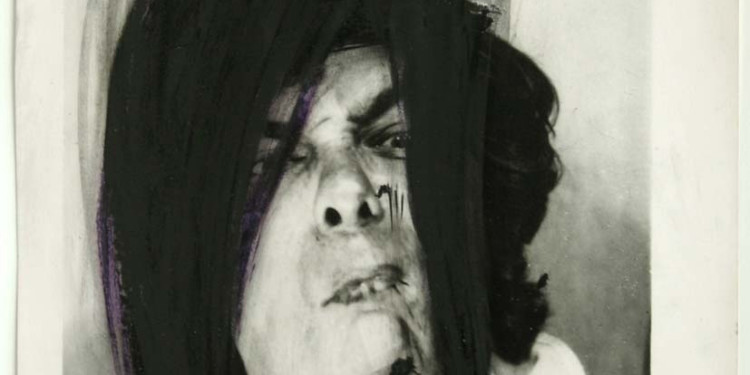

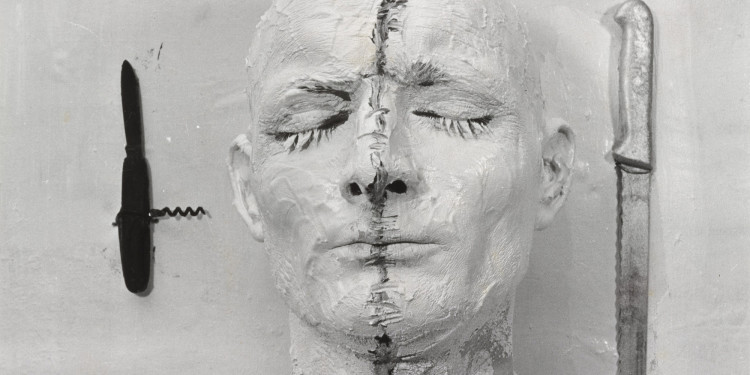

The face as a site for alteration and extreme expression is of particular interest to several artists in the exhibition. In his five-part work, Studies for Holograms (1970), Bruce Nauman poked, pulled, pinched, and kneaded his mouth, neck, and cheeks in extreme and cartoonish ways. For her 1972 work (Untitled) Facial Cosmetic Variations, Ana Mendieta used tape and make-up to mold and manipulate her face to create, at turns, disturbing and humorous results that reference the cosmetic changes women inflict upon themselves in the name of beauty. Lucas Samaras’s transformations in a series of self-portrait Polaroids from 1969–71 suggest the plasticity or mutability of identity itself. For these works, the artist utilized an array of wigs, pancake make-up, and props to transform himself into grotesque characters for the camera.

Other performances required a sustained, emotional engagement on the part of the artist. Bas Jan Ader’s particular brand of existential-based Conceptualism is crystallized in I’m too sad to tell you (1970), in which the artist cried in front of the camera. In 1971, Adrian Piper performed a time-lapse piece titled Food for Spirit. Inspired by an assignment to write a text on Immanuel Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason, Piper began fasting in order to isolate herself into a state of self-transcendence, and took pictures of herself in front of a mirror to insure reconnaissance of her own body. The ability of the camera to both freeze and extend a moment in time was also instrumental to the Japanese artist Mieko Shiomi. In Disappearing Music for Face (1966), Shiomi sequenced a series of film stills focusing on the mouth of Yoko Ono as her smile intermittently faded into a neutral facial expression. In Laurel Nakadate’s pictures from the Lucky Tiger series that she conceived of in 2009 during a road trip through the American West, the artist is seen riding a horse in a cropped T-shirt, doing a backbend in cowboy boots by the Grand Canyon, and striking a Playboy pose in her “lucky tiger” bikinis, rehashing photographic conventions inspired by 1950s-style “cheesecake” and camera-club pictures. Lorna Simpson’s multi-part work, May, June, July, August ’57 / ’09 (2009) also responds to the photographic conventions of posing for the camera. Simpson turned to the photographic archive as source material, combining found photographs of a young African-American woman who posed for hundreds of pin-up pictures in 1957 in Los Angeles with her own performative self-portraits, in which she replicates every outfit, pose, and setting of the original photographs. Through juxtaposition, repetition, and de-contextualization, a historical fiction arises, whereby the two women, despite the many differences that separate them, seem to be joined through a shared identity.

The exhibition includes both off-the-cuff and staged performative gestures of political dissent. Ai Weiwei’s photographic series Study of Perspective (1995–2003) reveals a spirited irreverence toward national monuments. Traveling to various landmarks—from the Eiffel Tower to Tiananmen Square to the White House—the artist photographed his own arm extended in front of the camera’s lens as he gave each marker the middle finger. Robin Rhode’s pictures, presented sequentially in storyboard format, record situations in which the artist interacts with a set of objects that he has drawn, erased and redrawn in black charcoal on dilapidated walls. Untitled, (Dream House) (2005) comprises a sequence of 28 color photographs in which Rhode mimics the act of struggling to catch a television set, a chair, and a car that appear to have been thrown at him from above. In reality, these items are drawn in cartoonish lines on an exterior wall. Referencing the South African New Year custom of tossing out old objects, the artist identifies society’s two opposing poles: consumerism and dispossession. Rhode’s pictures, like those of the other artists in Staging Action, attest to the myriad ways in which photography constitutes—not just documents—performance as a conceptual