SFIORERAI IL MIO DESTINO COME UNA FARFALLA | FONDAZIONE ALDA FENDI-ESPERIMENTI

SFIORERAI IL MIO DESTINO COME UNA FARFALLA*

Written and directed by Raffaele Curi

Experiments – Alda Fendi’s Foundation

Ex Mercato Ebraico del Pesce – Rome

13-18 April 2011

Text by Roberta d’Errico

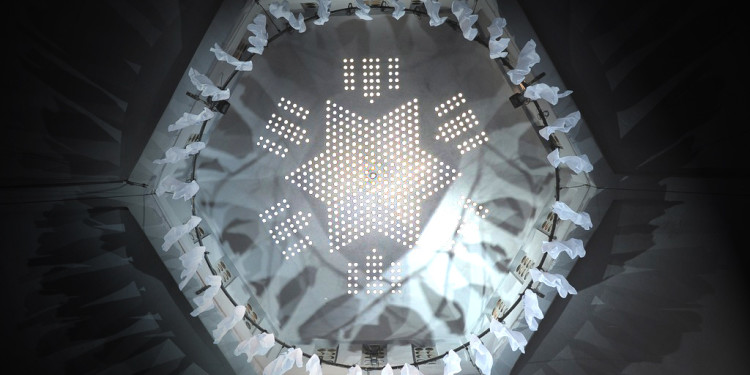

When the enormous doorway of the ex-Hebraic Fish Market is opened, we hear an overpowering music from the inside that wake and attract us magnetically. Once in we are engulfed by the circular structure immersed into music and blue and white lights.

The stage is put at opposite ends of the entrance, is connected to the place where onlookers stand through a small transversal footboard. The footboard and the stage are carpeted of bay leaves and such a sight induces us to a sacral approach. Alongside the walls of the hall some words are scrolling but we are not able to understand, whereas it is easy to guess the religious sense, regardless of whose religion they are.

The place selected for the performance sees the audience in a state of tension and historical consciousness: looking up, in the centre of dome, a cross of David sculpted in stone stands out in sharp relief. To function as an addition, a multitude of white shirts hung from a circular framework; we do not know if according to raffaele curi’s thought, their office is to protect or just be a post-modern materialization of a curtain.

On the bottom of the stage they project onto a giant screen the images of women forming a plastic composition through their body expressiveness captured by snap. They have on a white vest whose lengthened sleeves create a well thought out web of lines. The writing “This should be eternal white” alternates to the image. Music dies away. Just a moment of silence.

We are out of place because of the unannounced appearance on stage of Kim Carnes; she throws us back into the eighties singing live the famous Bette Davis’ Eyes. But we feel comfortable to hear it. The song as everybody knows is speaking of a woman with the eyes of Bette Davis; those deep, expressive eyes that made her a beauty in spite of Hollywood aesthetical models. Her eyes evoke the dolce stil novo love that through the eyes reaches the heart; the spiritual, absolute love, that is identified with the good of the beloved and the good of the other one.

We are into the performance core. A warm and quite voice whispers to our ears that the true wealth is to preserve the child’s frailty during his life because when the man is acrimonious and dry like a piece of wood, he is going to die.

A man with an old shabby cloth on and a bucket comes on stage. He looks like the Kafkaesque Knight of the coal, poor and cold man, who refers to the commandment “thou shalt not kill” asking for some coal on account.

Out of stage, his image comes into sight projected onto the screen and from there it travels at full blast all around the hall, outrunning the light, as if he wanted to turn the clocks back. His image is transformed into white and orange lines which recall to our mind those of Daniel Buren. The same previous man comes on stage but with a striped suit on. He becomes himself a Buren’s work and the famous stripes of the French artist remind us those of the concentration camp.

The stage is again an empty space.

A naked youth appears. The theatrical setting, keenly employed by Raffaele Curi, inform us of the purity of the nakedness preserved from the obsessive insult of the media. The youth’s body is placed near the Darwinian image of the evolution of the species tracing him back to its animal origins and saving him from a malicious vision. Again the stage is empty.

An incense burner put on a tripod is took on stage and bay leaves are burned: as in a Wagnerian gush the olfactory perception is joined to the visual and aural one.

A priestess, the Pythian of the antiquity, heads towards the stage crossing the audience. Prior to climb the stage, she goes up and down the footboard nervously as if she did not want to carry out her own oracle. When she is in front of the censer burning, she drops the bay in her hands. The scented smoke gives off filling us with exhilaration. The priestess’ glance is severe, angry, she delivers a message of disapproval.

On the screen, it appears Piero della Francesca’s fresco “La Resurrezione”. A black blind is lowered to veil the Christ and keeping only the sleeping four soldiers in sight. Are we corrupt and guilty in such a way we deserve no Resurrection of the dead? Or perhaps is not the time yet we can be delighted thinking of Christ’s rebirth, in view of the fact that the performance took place a few days before Easter? Such are the questions we ask ourselves.

On the walls of the hall appear pieces of writings that give us a life lesson: never want what it is beyond our capabilities. It recollects us that our glory lies in our perfectible, vulnerable, weak being. When the stage is empty the naked youth is again on and he captures the centre scene of the square and compass, Masonic symbol, our ambition to ethics and to aim at perfection of man.

Another moment of the performance is marked by the projection of Italian playing cards on the walls of the hall. They change place and suit, as if they were playing with our fate, but their meaning is beyond, into the secular combinations of cultures and symbols that are hidden in them.

Now on the bottom of the stage and on either hand of the hall is projected a stylized image of a king, similar to that of the playing cards, a white line draws the outline on a black field. He is surrounded by unintelligible signs of a time honoured language. On stage, a naked boy and girl place themselves on both sides of the king. Slowly and unnoticeably the symbols on either hand of the hall, surrounding the king, start to vibrate and to float towards the youths. They become lights and then small coloured butterflies which go through the two young bodies, they go up, on high, and through the stage fly towards the audience. Even our fate has been brushed by the delicate and light beauty of the butterfly. Now the stage is empty again. On screen appear images of exiles, emigrants, social rejects, poor and hungry devils. An endless bird’s eye view fades out their faces, awaiting in line for a meal, a hope of a better life.

Afterwards the screen is filled with a butterfly, the two naked youths come back on stage to the tune of “Un bel dì vedremo” **(Madame Butterfly’s aria, G. Puccini), in a pop and Arabic swing version that take us faraway. The youths are one opposite the other, in the beautiful act of the sexual union with a sweet and explosive musical backing. Behind, on the screen appear the words “After 20 centuries, the love is still sixteen years old”, Up, in the middle of the hall, the Star of David is enlightened and the shirts come down with vehemence to tell us that the performance is ended. We should like to remain longer in order to watch those two bodies together so innocent that pain us within a message that once was our own: pure, spiritual, physical love, for my love’s sake, for the other’s sake.

Roberta d’Errico

Theatre Editor

Translated by Salvatore Rollo – at salvatore_rollo@fastwebnet.it

*You will brush my fate just as a butterfly

**It will come a nice day we will be able to see…

Position the cursor on the images to view captions, click on images to enlarge them.

Posizionare il cursore sulle immagini per leggere le didascalie; cliccare sulle immagini per ingrandirle.

SFIORERAI IL MIO DESTINO COME UNA FARFALLA

Scritto e diretto da RAFFAELE CURI

FONDAZIONE ALDA FENDI – ESPERIMENTI

Roma Ex Mercato Ebraico del Pesce, 13-18 aprile 2011

Testo di Roberta d’Errico

Quando si apre l’enorme portone dell’ex Mercato Ebraico del Pesce, dall’interno, una musica potente ci risveglia e, magneticamente, ci attrae. Una volta dentro, siamo fagocitati dalla struttura circolare del luogo, immersi nella musica e nelle luci blu e bianche.

Il palcoscenico, posto in direzione opposta all’entrata, è collegato al luogo degli astanti attraverso una piccola pedana trasversale. La pedana e il palcoscenico sono ricoperti da foglie di alloro e questa visione induce un atteggiamento sacrale. Lungo le pareti laterali della sala scorrono parole a noi incomprensibili, ma non è difficile intuirne il senso religioso, qualunque sia la loro appartenenza. Il luogo prescelto per lo spettacolo non può non disporre lo spettatore in una condizione di tensione e di coscienza storica: levando lo sguardo, al centro della cupola, una croce di Davide scolpita nella pietra campeggia sulla sala. A farle da corollario, una schiera di camicie bianche appese ad una struttura circolare, e non sappiamo se, nella visione di Raffaele Curi, la loro funzione sia di protezione o una materializzazione di sipario postmoderno.

Un enorme schermo sulla parete di fondo del palcoscenico inizia a proiettare l’immagine di donne che formano una composizione plastica attraverso la gestualità dei corpi fermata nello scatto fotografico. Indossano una maglia bianca le cui maniche allungate creano un intreccio ben studiato di linee. Ad interrompere ciclicamente l’immagine appare la scritta “Questo dovrebbe essere bianco assoluto”. La musica svanisce. Un attimo di silenzio.

Siamo spaesati dall’improvvisa apparizione in scena di Kim Carnes che ci catapulta negli anni ’80 cantando dal vivo il celebre brano Bette Davis Eyes, ma la sua sonorità ci fa sentire a nostro agio. La canzone, com’è noto, parla di una donna che ha gli occhi di Bette Davis, quegli occhi profondi ed espressivi che la resero bella a dispetto dei canoni estetici hollywoodiani. Gli occhi di Bette Davis evocano l’immagine stilnovistica dell’amore che, attraverso gli occhi, arriva al cuore, l’amore spirituale, assoluto, che si identifica con il bene dell’amato e dell’altro.

Siamo entrati nel cuore dello spettacolo. Una voce calda e calma ci sussurra che il vero tesoro è mantenere la fragilità del bambino nella vita perché quando l’uomo è rigido e secco come il legno è pronto alla morte.

Un uomo con un vecchio abito dismesso e un secchio appare in scena. Sembra rievocare il cavaliere del carbone kafkiano, povero e infreddolito, che si appella al comandamento “non uccidere” chiedendo un po’ di carbone a credito.

Uscito di scena, la sua immagine appare proiettata sullo schermo e da lì percorre a ritmi sfrenati il giro della sala, più veloce della luce, quasi volesse portare indietro il tempo. La sua immagine si trasmuta in linee bianche e arancioni che non possono non richiamare quelle di Daniel Buren. Entra in scena lo stesso uomo di prima, ma con una divisa a righe. E’ diventato egli stesso un’ opera di Buren e le famose strisce dell’artista francese rimandano ora a quelle delle divise dei campi di concentramento.

La scena è di nuovo vuota.

Appare un ragazzo nudo. La cornice teatrale, acutamente utilizzata da Raffaele Curi, ci comunica il candore della nudità preservata dall’ossessivo oltraggio dei media. Il corpo del ragazzo è posto accanto all’immagine darwiniana dell’evoluzione della specie riconducendolo alle sue origini animali e sottraendolo ad una visione maliziosa. Di nuovo la scena è vuota.

Sul palcoscenico viene portato un incensiere posato su un tripode e sono bruciate foglie di alloro: in un impeto wagneriano, la percezione olfattiva si inserisce in quella visiva e uditiva.

Una sacerdotessa, la Pizia dell’antichità, si dirige verso il palcoscenico attraverso il luogo riservato agli spettatori. Prima di salire sul palcoscenico, sale e scende nervosamente dalla pedana quasi non volesse compiere il suo oracolo. Quando si trova di fronte all’incensiere che arde agita l’alloro che tiene nelle mani espandendo il fumo profumato che ci invade e ci inebria. Lo sguardo della sacerdotessa è severo, arrabbiato, il messaggio che porta è di disapprovazione.

Ora sullo schermo appare l’immagine dell’affresco La resurrezione di Piero della Francesca. Una tendina nera si abbassa velando la figura del Cristo e lasciando al nostro sguardo solo l’immagine delle quattro guardie addormentate. Siamo a tal punto corrotti e colpevoli da non meritare più la Resurrezione? O forse, visto che la rappresentazione si è svolta pochi giorni prima di Pasqua, non è ancora arrivato il momento di bearci nel pensiero della Rinascita del Cristo? Queste le domande che annebbiano la mente.

Sulle pareti della sala appaiono scritte che ci impartiscono l’insegnamento di non aspirare mai a ciò che va oltre le nostre possibilità, ricordandoci che la nostra bellezza risiede nel nostro essere perfettibili, fragili, deboli.

Quando la scena è vuota riappare in scena il ragazzo nudo che conquista il posto al centro del simbolo massonico della squadra e del compasso, aspirazione alla moralità e alla perfezione dell’individuo.

Un altro momento della rappresentazione è scandito dalla proiezione sulle pareti della sala di carte da gioco italiane. Cambiano posto e figura, quasi stessero giocando con il nostro destino, ma il loro significato va oltre, nella secolare miscidanza di culture e simboli che in esse si nascondono.

Ora sul fondo del palcoscenico e ai lati della sala viene proiettata l’immagine stilizzata di un re, simile a quello delle carte da gioco, una linea bianca ne disegna il solo profilo su fondo nero. Lo circondano indecifrabili segni di una lingua antica. Sulla scena, un ragazzo e una ragazza nudi si dispongono ai lati della figura del re.

Lentamente e impercettibilmente i simboli che circondano la figura del re, ai lati della sala, cominciano a vibrare e a fluttuare verso la scena. Divengono segni di luce e poi piccole farfalle colorate che attraversano i corpi dei due giovani, salgono su, in alto, e attraverso il palcoscenico volano verso la sala. Anche il nostro destino è stato sfiorato dalla fragile e leggera bellezza della farfalla.

Ora la scena è di nuovo vuota. Sullo schermo compaiono immagini di esuli, emigranti, emarginati, gente povera e affamata. Una carrellata sfuma infinita sui loro volti in fila in attesa di un pasto, di una speranza di vita migliore.

Poi una farfalla riempie lo schermo, i due giovani, nudi, rientrano in scena sulle note di Un bel dì vedremo in versione pop con ritmi arabeggianti che ci portano lontano. I due corpi si fermano uno di fronte all’altro, nella potenza dell’atto della congiunzione amorosa. Una musica dolce ed esplosiva li accompagna. Dietro di loro, sullo schermo, appare la scritta “Dopo 20 secoli, l’amore ha ancora sedici anni”. In alto, al centro della sala, la stella di Davide si illumina e le camicie scendono irruentemente a dirci che la rappresentazione è finita. Vorremmo restare ancora, ad osservare quei quei due corpi così innocentemente uniti che ci fanno soffrire nella distanza di un messaggio che un tempo ci apparteneva, amore puro, spirituale, fisico, per il bene dell’amato, per il bene dell’altro.

Roberta d’Errico

Theatre Editor

1 Comment

Sono poeta e scrittrice e ti mando una mia poesia ” Non ti credevo farfalla,

ma appassita corolla di gelsomino /invece a un tratto / hai disteso le ali / e sei volata via, / bianca nell’azzurro, / come velo di sposa.”

Da ” Giochi di luce e d’ombra” di Lidia Colla Ed. Gruppo Albatros Il Filo 2010