SIGALIT LANDAU’S INTERVIEW – ONE MAN’S FLOOR IS ANOTHER MAN’S FEELINGS | ISRAELI PAVILION

SIGALIT LANDAU

« ONE MAN’S FLOOR I S ANOTHER MAN’S FEELINGS »

Israeli Pavilion

54 th International Art Exhibition, La Biennale di Venezia

June 4 – November 27, 2011

http://www.sigalitlandau.com/page/biennale.php

Sigalit Landau’ s interview by Jean de Loisy

The Pavilion is composed of stories, things and gestures that are juxtaposed. Among them, I weave very open meanings that may be read together as a poem or a metaphor for our common destiny. But above all, the situations I have juxtaposed, which together find their unity, allow for an experience. That is to say, I have combined emotional, political and aesthetical sensations and circumstances that turn or appeal directly to our consciousness.

Politics and poetry exist in my works mix and clash. When I look ‘the ugliness and pain of life in the eye’, I know reasons for everything … whatever I feel is political. This is the force, the coercion of the place in which I live, But, the materials I use are constructive.

I blocked day light out from the ground floor of the pavilion, and kept out the Giardini ambience by turning the entrances glass walls into ordinary walls. The pavilion is no longer ‘floating’ on air and on light – merely supported by thin white pillars. I installed a heavy iron sliding entrance door, a door into an industrial space. The façade no longer looks like an entrance to a culture-house but rather like a back door of a huge university or factory.

I knew from my previous work in this pavilion, that in order to support the middle level of the building leading the visitor from the “transitional” lower level to the spacious 3rd level, architect Rechter, created a sealed out space.

I am attracted to places that are disregarded, hide outs, architectural ‘pockets’, informal and ‘in-between’ spaces; I made a hole in the wall of this hidden space and re-invented it so that I could place the heart of my installation [the pump] in the ‘intestine of the building’ which was full of earth and debris. I worked as much as I could to take out this earth… It felt like an escape, and a search, and a search for water… also like a release from ‘territorial constipation’.

This ‘room’ is the heart of this 50’s Pavilion, its subconscious. A room that has been secret for a long time filled with black earth, obscure like our intestines or like other concealed parts of the body. I want it to have a status that is equal to the other parts, like everything that has been neglected and that the art must reveal.

A sculpture made of pipes runs across the pavilion’s ground floor. This is ‘a thirst’ as the prolog to the exhibition, a thirsty existence that tries to draw water from the earth. Having used water metaphorically for years, this time I use it in an absolutely concrete manner. And the fact that this exhibition is being held in Venice, a city irrigated by water on all sides, is also a reason, an unconscious and unreal reason, [as the Adriatic sea is salty].

In the south of Israel, one can see kilometers of pipes for channeling water that does not quite exist. This is why the country is covered with these pumps that suck at the earth in search of confined aquifer and ground water from deep below. This is a part of a familiar esthetics in my region.

In the dessert they are more visible than in the greener north of Israel. Sealed cages in the middle of nowhere -with intricate combinations and variations of pipe systems, thick and white [like the pillars used to support the pavilion], they are constantly pumping slowly to bring water from hundreds of meters below ground level.

I set up a system to pump the “aqua alta”, of the Venetian lagoon … into and out of my “thirsty” installation. But after doing so – I preferred to waste less electricity and I let the water circulate in a cycle throughout the various pipe sculptures. The pipes tremble slightly, and are cooled by the water flow. The space resembles a machine room. The machine room exposes and demystifies functions on the one hand, but also supports and enables the illusion and esthetic world above it … Water is a metaphor for knowledge, truth, and love – Real water, and absent water, poison water, frozen water and sweat are mirroring each other in the show.

Sigalit Landau is the selected artist to show at the Israeli Pavilion for the 54th International Art Exhibition – La Biennale di Venezia,

Opening to the public, June 4th, 2011.

Sigalit Landau’s committed and poetic approach turns personal questions, be they philosophical or political, into universal quests. To achieve this, the artist combines installation, sculpture and objects, videos and performance. Her work crystallizes a collection of ideas through a single image, object or action, rendering them symbolic, much like in her “Barbed Hula” video, where she appears on a beach in Israel naked, performing a hula hoop dance using a ring of barbed wire.

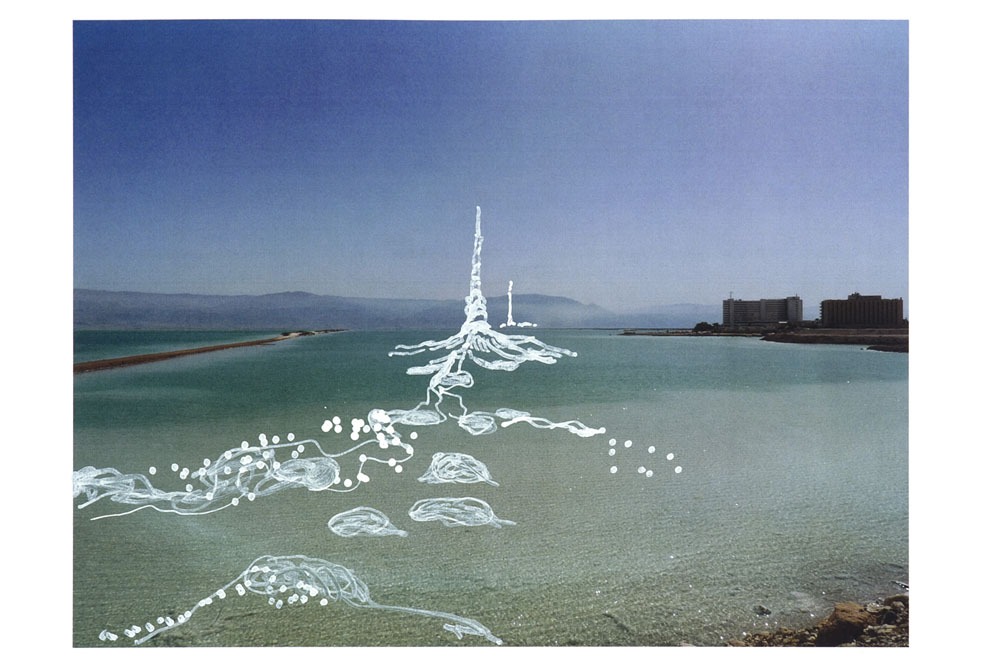

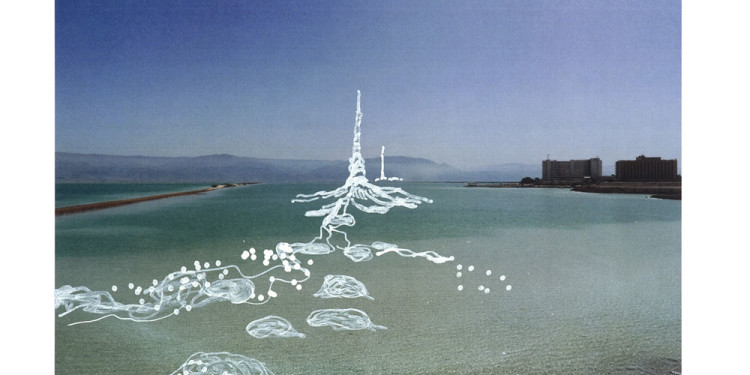

For several years, Sigalit Landau has been involved in a deep relationship with the lowest place on earth, the Dead Sea (456m below sea level). She reacts, as an artist, to the peculiarities of this site; this damaged place which holds within it the region’s geopolitical history, and is the scene of an ongoing ecological disaster. This is the place she has chosen to stage her unique oeuvre, inspired by her continual attraction to embody the ritual linked to memory. This is also where she orchestrates her exploration of the archaeology of the present. The key themes of Sigalit Landau’s exhibition will be water, soil, and salt. Through these basic elements the artist will explore issues of existence and survival: the interdependence of people and nations in her native region, and their common interlinked future.

Landau, notorious for her complex site-specific installations, like those presented at the Tel Aviv Museum and Kunst-Werke Institute for Contemporary Art, Berlin, is planning a poetic and multilayered installation for the Israeli Pavilion at the 54th International Art Exhibition – La Biennale di Venezia. The exhibition is yet another step in Landau’s ongoing exploration of the tensions between public and personal issues and space.

Based on Landau’s historical research, the launching point for the installation is the small three tiered Pavilion building in which her exhibit will take place – a structure designed in the modernist style. The title the artist has given to her work for the pavilion, “One man’s floor is another man’s feelings” is a variation on the familiar saying “One man’s floor is another man’s ceiling”, Through this title, the installation will evoke the interdependence of human beings and the sharing of riches.

The presence of water in the piece symbolizes blood irrigating the body and this liquid so scarce for billions of people, becomes a metaphor for the knowledge and feelings that connect us and organize our common destiny. Like salt deposited on an object or penetrating a wound, the journey that Sigalit Landau is plotting for the 54th International Art Exhibition – La Biennale di Venezia, crystallize the fears and hopes of these uncertain times.

The commissioning of the Israeli Pavilion is directed by Jean de Loisy and Ilan Wizgan.

_

The exhibition will be accompanied by a catalogue, designed by Noam Schechter that presents the latest works and combines discussions about some of Sigalit Landau’s previous work.

The catalogue includes some of the artist’s research process for this upcoming exhibition and also includes four essays (Jean de Loisy, Chantal Pontbriand, Matanya Sack and Ilan Wizgan) and is edited by kamel mennour and distributed by Les Presses du réel.

“The Freezing and Melting Point” by Ilan Wizgan

The Israeli pavilion in the Giardini of the Venice Biennale, with its distinctive history, geography and morphology, is the stepping-stone for Sigalit Landau’s project. The pavilion, first conceived in the late 1940s, was designed by Israeli architect Zeev Rechter, and unveiled in the mid 1950s. Venetian authorities allocated a site for the pavilion on the banks of the Giardini Canal, next to the US pavilion. Among the varied architectural styles of the national pavilions in the Biennale Gardens, between neo-Gothic and neo-Classical structures, Rechter chose to design a Modernist pavilion in the spirit of the Bauhaus and the International Style that characterized pre-State construction in Israel.

(…)

(As part of her preliminary preparations, Landau researched the circumstances of the pavilion’s construction, burrowed in the archives of its architect, and dug up every yellowing piece of paper that could possibly shed light on the process, from the stage of the initial concept (prior to the establishment of the State of Israel) to the final design. (…) In her typical fashion, Landau does not view the structure as a self-evident reality to which she is obliged to conform. She believes that it is the space that should serve the work, building for compromises and changes that sometimes include tearing down walls, sealing windows, making holes, digging, and the like.

Ground Floor

Upon entering the exhibition, the visitor finds himself in a space reminiscent of a machine room. On one side, between the two stairwells, a video work is projected onto the floor. The work depicts a group of men playing the Countries game – marking a circle in the sand, throwing knives into it, and dividing the territory between them. Their shouts slice the air, spreading throughout a space interlaced with an extensive system of water clocks and pipes leading from one to another, rising and falling, to converge at the other end of the space; there, they cross its borders and disappear into an aperture in the wall, while crossing another space that is caged between the pavilion’s floors, where they end – or perhaps begin – their journey in the large canal of water adjacent to the pavilion. Concealed in the caged space is a pump, the beating heart of the system, which propels the water through the pipes like blood through the body’s arteries. The water flows in a closed circle, incessantly originating from and returning to the canal, leaving faint sounds inside the space, the only evidence of the water’s hidden movement.

(…)

(…) Typically, a machine room is a concealed space in a structure, an area responsible for the functioning of the entire system but, as long as it continues to operate properly, we are neither aware of it nor exposed to it. Attention is directed to it when there is a fault or breakdown, just as we become aware of our bodies, our internal organs, only when they transmit pain or do not function. The exposed machine room, therefore, hints at the need for catheterization, or even real open heart surgery, in order to bring relief and resolve the problems addressed by the exhibition, including inequality between people, violation of the ecological equilibrium, and the distribution of resources and wealth among nations.

(…)

Upper floor

The spiral staircase leads the visitor directly to the upper floor. Unlike the bottom floor, this one is nearly empty. The relatively large space is entirely dedicated to a video film that is screened on a diagonal wall. In the film, cinematic in size and quality, a pair of shoes is shown in close up, covered with salt crystals, lying on a layer of ice. The shoes, which Landau previously dipped in salt water, underwent a process of natural crystallization until they were covered with a thick layer of salt. Next, the shoes were flown to a frozen lake in Gdansk (Danzig), Poland – an area that in the not too distant past was the focus of a feud for possession between Germany and Poland – and placed on ice and, in a slow process, the shoes melted the ice until they fell into the hole they created. The sinking of the shoes is connected with a sense of melancholy, loss of control and even physical collapse, a condition in which “the ground plummets underfoot”. The size of the screen is significant since it embraces the viewer and sharpens and heightens the experience of being part of the installation.

(…)

Middle floor and courtyard

The middle floor was deliberately selected as the site for the exhibition’s central installation; the middle is both the average and the place where opposites can meet. This is also the floor that connects the two other floors into one entity, which here receives its full significance and meaning. Erected on this floor is an installation consisting of a round conference table with a wide-open gap in the middle and chairs around it. Scattered on the table are laptops and shown on their screens are scenes from a movie depicting a little girl hiding under the same table and tying together the shoelaces of the people engaged in debate; perhaps a prank, perhaps an innocent act intended to force the debaters to remain seated until they find a solution to the issue they are discussing. But it turns out that despite this, the debaters desert the conference table and flee barefoot, leaving their shoes behind them. From the loudspeakers concealed in the walls, the voices of the absent debaters are heard, speaking in Hebrew and Arabic, or in English with typical accents. The topic of the debate is the construction of a salt bridge that will connect the Israeli side of the Dead Sea to the Jordanian side. The discussion centers on practical and technical aspects of the concept of the bridge. Several white flags are propped against one of the walls, objects that Landau dipped in the Dead Sea until they were covered with salt crystals. An echo of the tied circle of shoes is also found in the courtyard, where a circle of bronze shoes, tied to one another, is located.

(…)

(…) shoes are the motif with the greatest presence in the exhibition and their location in the conference room increases their presence tenfold – twelve pairs of shoes (the number of the tribes of Israel). The circle of shoes tied to one another emphasizes the circle in which the debaters are trapped, unable to untie or open the knots. The shoes are also a metaphor for a state of wandering and being a refugee, subjects frequently addressed by Landau. Abandoned or grouped shoes are linked to the Holocaust in Israeli consciousness, as well as in Landau’s consciousness, and she explicitly referred to this subject in The Endless Solution exhibition. There, we also saw the presence of many boxes of shoes numbered 39-45, the years of World War II, as well as pairs of clogs scattered around the space. The most notable work dealing with shoes in the context of the Holocaust was created by Joshua Neustein, Georgette Bélier and Gérard Marks, and exhibited at the Jerusalem Artists House in 1969. This work made a very direct statement; thousands of pairs of shoes were placed in piles throughout the spaces of the House in a manner reminiscent of the piles of shoes found in the extermination camps, and even the manner in which such piles are displayed in various Holocaust history museums. Additionally, a row of bronze shoes (by Giola Pauer) was installed on the banks of the Danube River in Budapest (shoes of all types – men, women and children) in memory of Jews shot and thrown into the river by Nazi collaborators after being ordered to remove their shoes. In other contexts, the most famous shoe paintings are Van Gogh’s; some of these are reminiscent of the pair of shoes that Landau chose for her video work on the upper floor. Other well-known shoes are Andy Warhol’s, who repeatedly referred to shoes in the context of mass culture, and even as a type of self-portrait, in a manner similar to Van Gogh. One piece that Warhol entitled My Shoe Is Your Shoe even recalls the title of the current exhibition.

(…)

Without being overtly political, the exhibition (also) deals with the political in life and in art and, inherent in it, is criticism of nationalism and national ego, which always undermine rationalism and the positive potential inherent in cooperation and a just distribution of resources and wealth. Landau’s perspective is dialectic; from below, through the eyes of the little girl hiding under the table, as well as from above, over the heads of the men playing the Countries game. The exhibition attempts to bridge the gap between the childlike, innocent, ideal perception, and the world of adults, the estranged, calculated work of policymakers (political, social and economic), in a search for synthesis and unity of opposites.

Position the cursor on the images to view captions, click on images to enlarge them.

Posizionare il cursore sulle immagini per leggere le didascalie; cliccare sulle immagini per ingrandirle

« Construire un monde différent: une esthétique de la fluidité » par Chantal Pontbriand

« La communauté n’est pas le lieu de la Souveraineté. Elle est ce qui expose en s’exposant. Elle inclut l’extériorité d’être qui l’exclut. »1

Maurice Blanchot

Ainsi, à la page vingt-cinq du petit opuscule que Maurice Blanchot a écrit sur l’idée de communauté, s’énonce une définition de la question. Celle-ci nous guidera à travers le travail de Sigalit Landau, artiste israélienne, qui investit le pavillon de son pays à l’occasion de la 54e Biennale de Venise. La communauté, inavouable, selon le titre du livre, est un éternel recommencement et demande qu’il y ait une attention constante qui soit portée vers la question de ce qui réunit et de ce qui peut potentiellement faire en sorte qu’un être-ensemble puisse exister, ou que l’on puisse (co)exister.

(…)

La mer Morte et l ’eau comme substrat à une esthétique

Sigalit Landau est fascinée par la mer Morte. Celle-ci est menacée par les changements climatiques tout autant que par l’intervention directe de la main humaine. Ce grand lac sépare Israël, la Jordanie et les territoires de l’Autorité palestinienne.

Chaque année, le niveau de cette étendue d’eau baisse d’un mètre. À ce rythme, la mer Morte est sérieusement menacée. Il s’agit d’un phénomène naturel extraordinaire, vu la densité saline de l’eau. Celle-ci est d’environ 33 % (par comparaison avec l’océan où elle est de 2,5 %). Presque aucun organisme vivant ne résiste à cette eau, qui contient en revanche des minéraux tels que le magnésium ou le chlorure de sodium en quantités importantes. Ceux-ci sont au coeur d’exploitations industrielles qui contribuent à la richesse des pays concernés. Le risque écologique comprend par conséquent des défis économiques et géostratégiques majeurs. Plusieurs solutions ont été envisagées au fil du temps, mais rien de concluant n’apparaît à l’horizon pour l’instant.2

Les oeuvres de Sigalit incorporent ce qu’on peut appeler une pensée sur la mer Morte et sur ce qu’elle représente pour l’humanité. Et même au-delà des grands enjeux, ce qu’elle suggère pour la vie humaine, la vie intime, tout autant que pour la vie en commun et ses périls. Cette étendue d’eau remarquable à tous points de vue, ressource naturelle, économique, touristique, lieu de partition politique, Sigalit Landau l’envisage comme un espace à réinventer. Le réel devient sous son regard et à travers ses interventions un lieu d’investissement sensible et de transformation. Elle développe un regard autre sur les enjeux, une différence qui s’affirme par une logique qui ne passe pas par les solutions habituelles.

(…)

Le Pavillon comme dispositif

Intitulée One Man’s Floor is Another Man’s Feelings, un jeu de mot sur l’aphorisme anglais « One man’s ceiling is another man’s floor »[Le plafond des uns est le plancher des autres], popularisé par la chanson de Paul Simon, l’installation du Pavillon invente un dispositif à partir de son architecture même, où se fabriquent des émotions et des sensations. Sigalit investit ce lieu à partir d’un autre temps, le sien, qui n’est plus celui des années 1950, utopistes et modernistes, où les nouveaux courants architecturaux ont connu une emprise particulière dans la ville de Tel-Aviv, emblème d’un pays nouveau. Déjà, dans les années 1930 et 1940, une forte influence du Bauhaus laisse sa marque sur celle qui deviendra la Ville blanche. Zeev Rechter en est un des principaux exégètes. Le Pavillon de Venise pousse l’esthétique typique du Bauhaus israélien (la réduction des ouvertures à cause du climat) encore plus loin. Le bâtiment ne comporte aucune fenêtre et la façade est un mur aveugle, ce qui peut faire penser au courant brutaliste. Dans ces années modernistes, dominées par l’esprit du white cube mis en avant par le directeur du MoMA, Alfred Barr, un lieu d’exposition devait, autant que possible, ne pas recevoir de lumière naturelle.

Ce précepte visait à préserver les oeuvres et à en mieux contrôler les conditions de visibilité. On peut penser qu’il contribuait aussi à augmenter l’aura autour des oeuvres, à pousser à la limite le caractère exceptionnel et quasi sacré de cellesci, ce qui encore aujourd’hui se traduit par la cote des artistes au sein du marché de l’art. Le MoMA contribua à créer le phénomène glorifiant l’abstraction américaine, puis à consacrer son triomphe. C’était l’époque où l’art se valorisait à travers des valeurs de transcendance et de virilité qui, bien qu’elles perdurent encore aujourd’hui, ne représentent plus la seule voix, ou voie, dans le champ de l’art.

Le travail de Sigalit est en résonance avec ces changements importants. Elle entre en dialogue avec l’architecture du Pavillon et les idées qu’il véhicule, tant sur le modernisme que sur la situation géopolitique d’Israël. Elle s’y adresse non pas comme féministe, mais certainement avec une disposition féminine, telle qu’on la repère dans les écrits de Luce Irigaray par exemple.

Elle introduit dans le Pavillon de la fluidité et de la sensibilité, de l’ouverture aux sens et à leur polyphonie. Dans une démarche analogue à celle qu’elle développe autour de la mer Morte, elle travaille le Pavillon en tant qu’espace sexué (Irigaray). Elle s’adresse aux sens du spectateur, qui devient ici promeneur sur un territoire qu’elle réinvestit de sa présence de femme et d’artiste d’Israël aujourd’hui. Elle joue avec les sens, parce que ceux-ci complexifient ce qui est donné à comprendre par le dispositif mis en place. Les sens confèrent un supplément de sens, voire une polyphonie, à cette architecture monolithique, rationnelle et (plus ou moins) efficace, ni villa ni lieu d’exposition.

1 Maurice Blanchot, La Communauté inavouable, Minuit, 1983, p. 25.

2 La Mer Morte est en liste pour être classée comme l’une des sept merveilles de la nature par New Seven Wonders, une association soutenue par les Nations Unies. Cette décision est prévue pour l’automne 2011, et précipite les discussions tant sur le plan écologique qu’économique.

(…)

Cet espace ingrat en termes de « lieu d’exposition », Sigalit l’investit pour ce qu’il est, un lieu propre aux infrastructures, un lieu d’interconnection avec l’urbain, le réseau collectif qui forme le tissu urbain ou l’espace de vie en commun. (…)

(…)

Ce qui va advenir

La sortie mène à une terrasse où le spectateur, transformé en « promeneur» donc depuis qu’il a mis le pied dans ce Pavillon (je pense à Walter Benjamin en utilisant ce qualificatif, et à son engouement pour les « passages » comme lieux d’expériences multiples et inusitées), se retrouve avec d’autres comme lui devant un cercle de chaussures en bronze. Ce cercle évoque la communauté ou le choeur, le chorus, ce rassemblement qui lie plusieurs voies pour n’en faire qu’une, une voie unique qui n’existe que dans le moment présent, un présent toujours renouvelé et réinventé. Cette voie est la voix (et la voie) de l’événement, ce qui n’existe qu’une fois dans certaines conditions, toujours à recréer. Le cercle en bronze évoque bien ce moment des moments, le transforme en « monument », soit, et dans un double mouvement, en signale tout autant l’importance que l’absence. Les chaussures, de bronze noirci, ont été moulées sur des chaussures usagées ; elles sont d’hommes et de femmes, de vieux, de jeunes, de gens qui travaillent ou non et qui gravitent dans différentes sphères de la vie sociale.

Nous nous trouvons ici, sous le ciel que cette terrasse ouverte nous permet de retrouver, dans un moment de communauté sans communauté, dont l’horizon est dans un état de suspension, entre la réalité et le désir. Posées au sol, les douze paires de chaussures (douze comme les douze apôtres ou les douze tribus d’Israël) « parlent » de territoire, de rassemblement et d’appropriation, et renvoient au bien commun de tout homme, celui de porter des chaussures, élément de vie. Le promeneur s’y reconnaît, lui qui porte aujourd’hui comme demain des chaussures, et qui les porte dans le même espace que celles qui sont produites et données par l’artiste. Tous gravitent dans le même territoire, dans le même espace commun, potentiellement commun.

(…)

Biographies

SIGALIT LANDAU was born in Jerusalem. She lives and works in Tel Aviv. Her work has been shown in solo exhibitions at the MoMA, the Museum of Modern Art, New York; at the Gallery kamel mennour, Paris, at the Kunst-Werke Institute for Contemporary Art, Berlin; at the Tel Aviv Museum of Art, Tel Aviv; and the Witte de With Center for Contemporary Art, Rotterdam. Sigalit Landau’s work figures in important public collections: Israel Museum, Jerusalem; Kunstmuseum Kloster Unser Lieben Frauen, Magdeburg, Deutschland; Pompidou Center, Paris; The Tel Aviv Museum of Art, Tel Aviv; The Jewish Museum, New York City; The Brooklyn Museum, New York City; Magazine 3, Stockholm; Museo de Arte Contemporaneo de Castilla y Leon, Musak, Leon, Spain; Museos Archivos Y bibliotecas City of Madrid, Spain; Museum of Modern Art, New York.

—

JEAN DE LOISY is preparing as an independent curator the exhibition Monumenta with Anish Kapoor, at the Grand Palais in May 2011, and an exhibition on Shamanism for April 2012 at the Quai Branly Museum in Paris. Jean de Loisy has occupied positions in key cultural institutions and curated major exhibitions such as “Hors Limites – l’Art et la Vie” in 1995 or “Traces du Sacré” at the Georges Pompidou Center, Paris in 2008 and as “A Visage Découvert” at the Cartier Foundation, Paris in 1992 and La Beauté in Avignon in 2000.

—

ILAN WIZGAN is an independent curator who lives and works in Tel Aviv. He is preparing a traveling exhibition showcasing 15 Israeli contemporary artists to be shown in several museums in the United states in 2013, as well as two solo exhibitions of Israeli artists for the Ein Harod Museum (2012) and Baram Museum (2013), both in Israel. Ilan Wizgan has occupied positions in key cultural institutions in Israel, such as the Israel Museum, Jerusalem and the Art Focus Biennial, Jerusalem. He was artistic director of the first Jerusalem Biennial of Works on Paper (2002) in Jerusalem, has curated exhibitions such as Urban Tales (2006), outdoor video installations in Tel Aviv, The Cyprus Case, in 2005 at the Artists’ Residence Gallery, in Herzliya, In the Name of the Land, in 1998 at the Artists’ House, Jerusalem, and was commissioner for several Israeli exhibitions in the biennials of Venice and Sao Paolo.

—

CHANTAL PONTBRIAND is an art critic and curator, until recently Head of Research and Development at the Tate Modern in London, she is the director and founder of the contemporary art magazine PARACHUTE (1975-2007). From 1982 to 2003, she was the director of the FIND (Festival international de nouvelle danse)- (International Festival of New Dance) in Montreal.In 2009, she was the curator invited to the Jeu de Paume in Paris for HF| RG [Harun Farocki | Rodney Graham] and in 2010, she organized the Higher Powers Command exhibitions (fromone of Sigmar Polke works, 1968)- Lhoist Collection, Belgium, and The Yvonne Rainer Project, BFI Gallery, London. She has been a consultant for: museology, cultural policies, international juries, Acquisition committees, bursaries and government grant awarding. She has received many bursaries and prizes like le Grand Prix de la Ville de Montréal for the Festival international de nouvelle danse. Her publications include: Fragments critiques, 1998, Communauté et gestes, 2000, Contemporanéité et communauté (to be published), Jeff Wall (to be published), adding up to over 200 reviews and catalogues.

—

MATANYA SACK is a partner in Sack-Reicher Architecture and Landscape, based in Tel Aviv and London. She is teaching at the Architecture Department in Bezalel Academy of Arts and Design, Jerusalem, and at the Landscape Architecture Department in the Technion, Israel Institute of Technology, Haifa. She was co-curator of the exhibition Zeev, on the early work and thought of the architect Zeev Rechter (1899-1960), in 2009. Her work at the ETH Zurich received Award of Excellence from the American Society of Landscape Architects (ASLA 2009). Her recent built work includes “Green to Blue: Street Production” – an ecological infrastructure on the Mediterranean coast in Bat Yam, as part of the International Biennale of Landscape Urbanism 2010.

No Comment