CHRISTIAN DOTREMONT. LOGOGRAMMES – CENTRE POMPIDOU | PARIS

Christian Dotremont

Logogrammes

12 October 2011 – 2 January 2012

Galerie d’Art Graphique

Centre Pompidou

Place Georges Pompidou, 75191 Paris cedex 04 – téléphone 00 33 (0)1 44 78 12 33 –

Text by Vittoria Biasi – translated by Salvatore Rollo. All Texts are 1F mediaproject copyright. All Rights Reserved.

The Christian Dotremont’s exhibition. Logogrammes is shown inside the Galerie d’Art Graphique at Centre Pompidou. It is born on Christian Dotremont’s thirteen works donation to the Cabinet d’Art Graphique by Pierre Alechinsky and his wife Micky as written by Alain Seban in his introduction.

Dotremont is an important figure for the literature and with relation to the plastic art. During 1941 in Paris he meets Paul Eluard, Pablo Picasso, Alberto Giacometti together takes part in the surrealist group “La Main à la plume” (1) and during 1948 he is the co-founder of the movement “Cobra” and the relevant magazine.

Cobra movement sees the birth in Paris on November 8. The members of the “Centre Surréaliste Révolutionnaire en Belgique” (2) (Christian Dotremont, Joseph Noiret) those one of the “Dutch experimental group” (Karel Appel, Constant, Corneille) and one member of the “Danish experimental Group” (Asger Jorn) meet at the Hotel Notre Dame to draw up the manifesto of the group Dotremont will name CoBrA from the initials of their home towns.

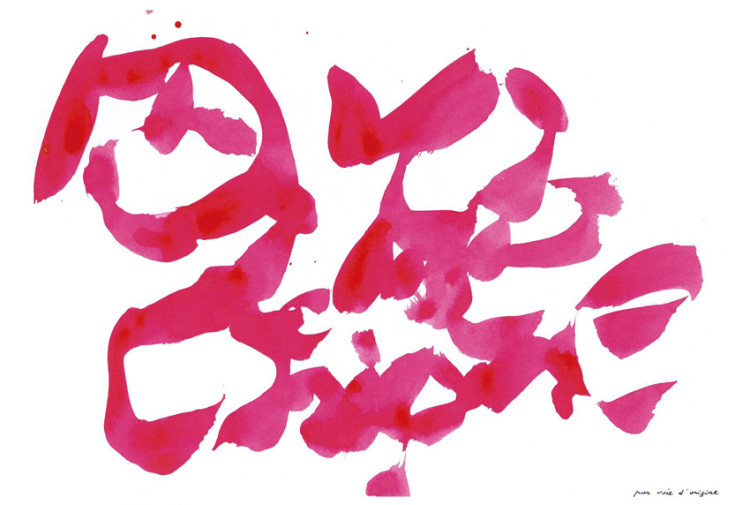

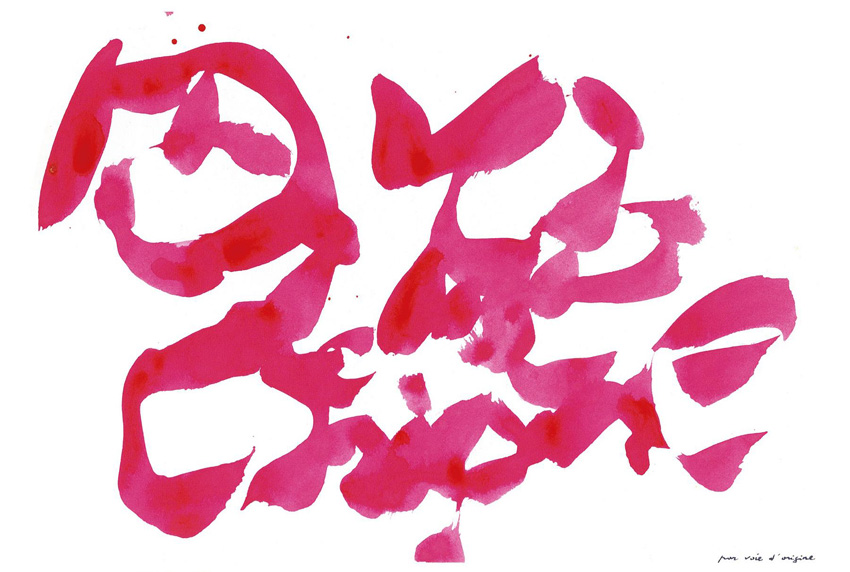

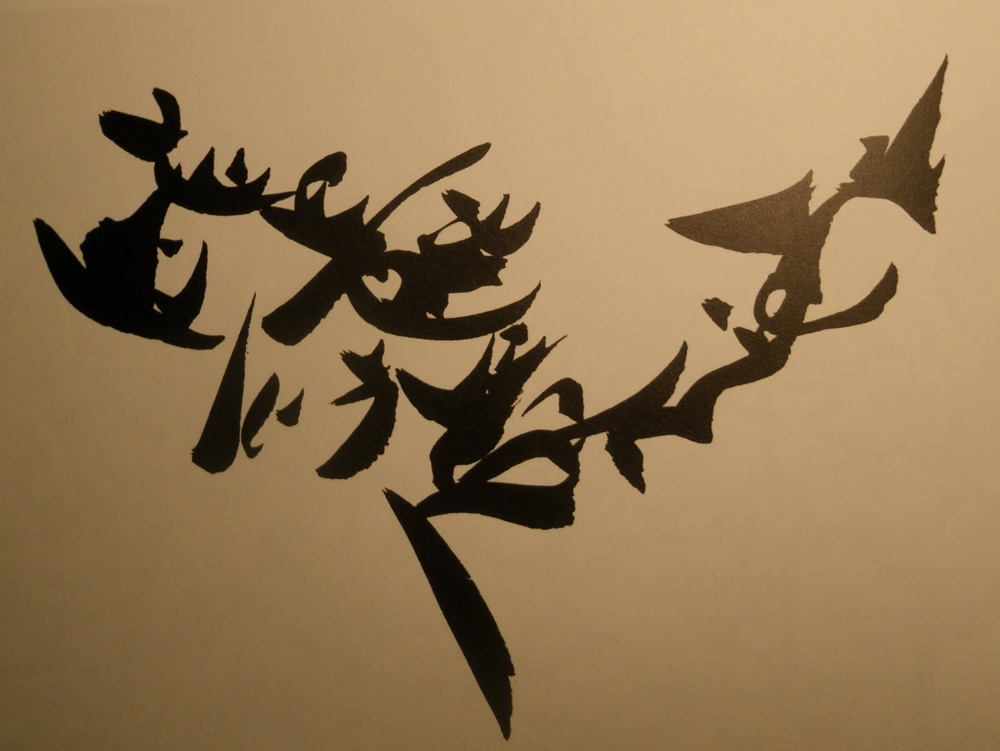

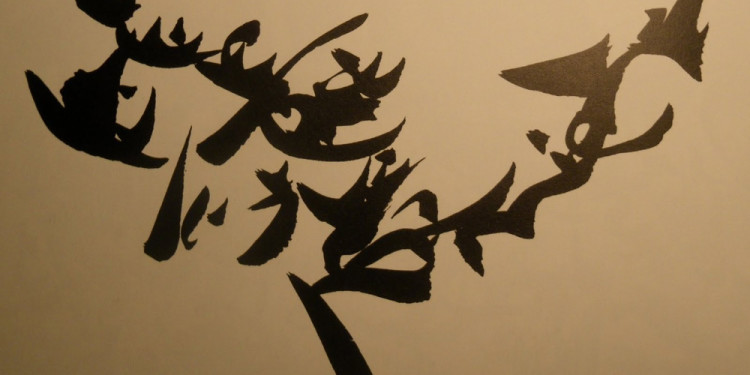

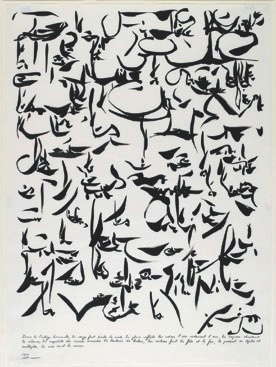

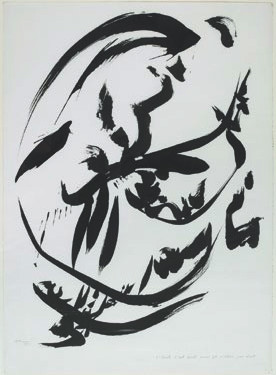

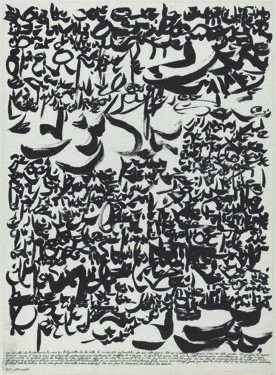

The exhibition Christian Dotremont. Logogrammes is the first display of logograms. The logogram connotes the art of Dotremont, it is his expressive feature, his invention, where the mark lives the evocative abilities of the writing between the traditional and the fictional alphabet, structured by lines and curves that strive for a meaning.

The commissioner of the exhibition Cristian Briend, Conservateur au Cabinet d’Art Graphique du Musée National d’Art Moderne (Room Supervisor for the Graphic Arts at the National Museum of Modern Art), starts his considerations on the artist writer’s works through the sentence “la vrai poesie est celle où l’écriture a son mot à dire” (the true poetry is the one in which the writing speaks its own mind), taken from “Signification et Signification” article printed on Cobra in 1950, the magazine ‘s editorial staff he was part of. In the essay, the artist meditates on the “dictatorship” of the printing, of the typewriting, because the author writes by hand first, and afterwards also in editorial way, like jazz is creativity and performance.

From 1948 on, Dotremont composes as a writer the works together with Asger Jorn and Pierre Alecinsky. His associating with the artists of CoBrA, according to Cristian Briend, could have been the circumstance and occasion that encouraged the artist towards the logogram, which absorbed all his creativity from 1962 to 1978.

1 The hand to the pen, t’sn

2 Belgium Surrealistic Revolutionary centre, t’sn

The experience of the tour in Finland, the acquaintance with the Lappish people, the meeting with the white fields, are the origin of his “logoneiges” and “logoglaces” (snow and ice logograms), writings and drawings in the snow which participate in a sort of inner Land Art. Dotremont is affected by the mankind’s imprint on the snow, which he recognizes being elements of a primitive language such as the exhibited works “Jure-moi de jouer” (3) (Virtaniemi-Nellim, 1976, transcription of “logoglace”, original picture of Caroline Ghyselen), “Serpent de neige sifflant au soleil” (Hissing snake of snow in sunlight) (Virtaniemi-Nellim, 1976, transcription of “logoneige”, original picture of Caroline Ghyselen) or also “Nouvelle sémantique” (New semantics) during same year.

The exhibition shows the works made during the period 1968-1978; it builds the artist’s pathway towards the language composition, that wants to get to the senses and the imaginative world, the space. During 1958 in his work made with Serge Vandercam writes the paintings-words “dans les silences des bois, j’écoute les odeurs de neige” (4). In the drawing, nearly a light and lone ideogram in the page space, the artist writer announces his history unknowing direction writing on the upper side “et comme si tous les traineaux-barques étaient tirés par l’invisible renne blanc” (1961). (5) During the next years the logograms seem to be the elaboration of a meeting among ancient alphabets, with possible references to cuneiform or Arabic writings.

The logograms extend over the sheet following a direction determined from within the same writing carried out by China ink and blacklead on a sheet of Indian paper.

Two passions are hidden within the works of Dotremont: Gloria and Lapland, for its winter landscapes …”à la fois rare et nombreuses, selon l’oeil, selon le champ, selon la mémoire stratificatrice des vues anciennes d’autres voyage… » (6) (C. Dotremont, Mémoire de neige, p. 18, Alentours, 2004). The poetic writing goes on following the succession of words/visions and comes to a stop only when the exhaustion asks for a break, it is a full stop, end and culmination of an emotion, of a direction, of a rhythm. The work of 1971 “ma main est un cheval qui trotte puis galope et bois les obstacles, et tout ça en regardant toujours l’éternité de l’herbe» (7) contains the way to live the feelings, to transcribe the inner wave on the right lower side of the page.

In “J’écris à Gloria” (8) the logograms are arranged in such a way the poetry can be welcome into the breadth of the paper. “Je suis ecrivant à Gloria/c’est pour la seduire/je travaille huit heures par jour,…” (8) as written by Dotremont continuing about his sense of doing, of drawing his sketches/brouillons full of meanings.

The poetic writing is the title of the work, it is the way to enter into the maze of feelings that are resident into an utopian place, transferred inside the work following an indecipherable idea.

The exhibition course arranges the rhythm of a sentiment that follows a galloping gait with accumulation of marks bent from left to right as sea waves, that in spite of the different winds, they manage to keep always the dominant direction, while the origin of movement stay deep, unknown, white.

In the last work in display “Vers sept heures du matin” (“about seven o’clock in the morning”) (1978, a year before his death) the logograms are swarm of marks, as always, of different dimensions accompanied of a composition that ends with a vision of a town covered in snow resuming its own life with the lights switching on everywhere and seem musical compositions written on the right vertical margin.

The exhibition brings back memories of his sensation, that Dotremont reveals to Caroline Ghyselen in 1976: he will never die in the white Lapland.

Vittoria Biasi – Art historian, critic and curator of international exhibitions

translated by Salvatore Rollo

Testo di Vittoria Biasi – Copyright 1F mediaproject.

La mostra Christian Dotremont. Logogrammes, presentata nella Galerie d’Art Graphique del Centro Pompidou, è nata, come scrive nella prefazione Alain Seban, Président du Centre Pompidou, in occasione della donazione di tredici opere di Christian Dotremont da parte di Pierre Alechinsky e della moglie Micky al Cabinet d’Art Graphique.

Dotremont, figura importante nella letteratura e nella relazione con le arti plastiche, nel 1941 incontra a Parigi Paul Eluard, Pablo Picasso, Alberto Giacometti con cui partecipa al gruppo surrealista “La Main à la plume” e nel 1948 è tra i fondatori del gruppo Cobra e dell’omonima rivista.

Il Gruppo Cobra nasce l’8 novembre a Parigi. I membri del “Centre surrealiste révolutionnaire en Belgique” (Christian Dotremont, Joseph Noiret), quelli del “Gruppo sperimentale olandese” (Karel Appel, Constant, Corneille) e un membro del “Gruppo sperimentale danese” (Asger Jorn) si riuniscono nell’hotel Notre Dame per redigere il manifesto del gruppo, che Dotremont chiama CoBrA dalle iniziali delle loro città di origine.

L’esposizione Christian Dotremont. Logogrammes è la prima mostra sui logogrammi. Il logogramma connota l’arte di Dotremont, è la sua cifra espressiva, la sua invenzione in cui il segno vive le possibilità evocative della scrittura tra l’alfabeto tradizionale e quello immaginario, strutturato con linee e curve che ambiscono ad un significato.

Il commissario della mostra Cristian Briend, Conservateur au Cabinet d’Art Graphique du Musée National d’art Moderne, inizia la riflessione sull’opera dello scrittore artista riportando la frase “la vrai poésie est celle où l’écriture a son mot à dire”, tratta dall’articolo “Signification et Signification” apparso nel 1950 nella rivista Cobra di cui lo stesso artista è stato redattore. Nell’articolo l’artista riflette sulla “dittatura” della stampa, della dattilografia, perché lo scrittore scrive dapprima con la mano, ma poi scrive anche con un senso redazionale, come il jazz è creazione e interpretazione.

A partire dal 1948, Dotremont compone opere con Asger Jorn e Pierre Alecinsky partecipando come scrittore. La frequentazione con gli artisti del gruppo CoBrA, secondo Cristian Briend, può essere stata la circostanza e l’occasione che ha favorito nell’artista la nascita del logogramma, su cui impegna la sua creatività dal 1962 al 1978.

L’esperienza del viaggio in Finlandia, la conoscenza della popolazione lappone, l’incontro con le distese bianche, sono all’origine dei suoi logoneiges e logoglaces, scritture e disegni sulla neve che partecipano ad una sorta di Land Art intima. Dotremont è emozionato dall’impronta dell’uomo sulla neve, in cui riconosce gli elementi di un linguaggio primitivo come nelle opere esposte Jure-moi de jouer (Virtaniemi-Nellim, 1976, transcription du logoglace, photographie originale de Caroline Ghyselen), Serpent de neige sifflant au soleil (Virtaniemi-Nellim, 1976, transcription du logoneige, photographie originale de Caroline Ghyselen) o ancora dello stesso anno Nouvelle sémantique.

La mostra espone le opere dal 1960 al 1978 costruendo il percorso dell’artista verso la composizione del linguaggio, che vuole raggiungere i sensi, l’immaginario, lo spazio. Nel 1958 nell’opera composta con Serge Vandercam scrive le parole-pittura “dans les silences des bois, j’écoute les odeurs de neige”. Nel disegno, quasi un ideogramma leggero e solitario nello spazio della pagina, l’artista scrittore annuncia l’inconsapevole direzione della sua storia scrivendo sul lato superiore “et comme si tous les traîneaux-barques étaient tirés par l’invisible renne blanc (1961)”. Negli anni successivi i logogrammi sembrano l’elaborazione di un incontro tra antichi alfabeti, con possibili riferimenti a scritture cuneiforme o arabe.

I logogrammi si distendono sul foglio seguendo una direzione dettata dall’interno della stessa scrittura eseguita con inchiostro di china e graffite su foglio di carta di Cina.

Due amori sono racchiusi nelle opere di Dotremont: per Gloria e per la Lapponia, per i suoi paesaggi invernali “…à la fois rares et nombreuses, selon l’oeil, selon le champ, selon la mémoire stratificatrice des vues anciennes d’autres voiages…”(C. Dotremont, Mémoire de Neige, p.18., Alentours, 2004). La scrittura poetica prosegue seguendo il succedersi di parole/visioni e si ferma solo quando lo sfinimento chiede l’arresto, che è un punto, fine e conclusione di un segmento emotivo, di una direzione, di un ritmo. L’opera del 1971 ma main est un cheval qui trotte puis galope et bois les obstacles, et tout ça en regardant toujours l’éternité de l’herbe racchiude il modo di vivere il sentimento, di transcrivere l’onda interiore sul bordo destro inferiore del foglio.

In J’écris à Gloria (1969) i logogrammi sono disposti in modo accogliere la poesia nel respiro del foglio. “Je suis écrivain à Gloria/ c’est pour la séduire/ je travaille huit heures par jour, …’’ scrive Dotremont, proseguendo sul senso del suo fare, del suo tracciare segni/brouillons densi di significati.

La scrittura poetica è il titolo dell’opera, è il cammino per entrare nel groviglio dei sentimenti, che hanno sede in un luogo utopico, che è trasferito all’interno dell’opera secondo un’idea indecifrabile.

Il percorso espositivo costruisce il ritmo di un sentimento che segue quasi un’andatura galoppante con l’accumulo di segni piegati da sinistra verso destra come onde del mare, che nonostante i diversi venti, riescono a tenere sempre una direzione dominante, mentre l’origine del movimento rimane profondo, sconosciuto, bianco.

Nell’ultima opera in mostra Vers sept heures du matin (1978, un anno prima di morire) i logogrammi sono sciami di segni, come sempre, di differenti dimensioni accompagnati lungo il margine verticale destro da un componimento che termina con la visione della città che riprende la vita sotto la neve con luci che si accendono ovunque e sembrano inizi musicali.

L’esposizione riporta alla mente la sensazione, che Dotremont confessa a Caroline Ghyselen nel 1976: un sentimento che nel bianco della Lapponia lui non morirà mai.

Vittoria Biasi – Storica dell’arte, critico e curatrice internazionale

Position the cursor on the images to view captions, click on images to enlarge them.

Posizionare il cursore sulle immagini per leggere le didascalie; cliccare sulle immagini per ingrandirle.

No Comment