THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART PRESENTS SITE-SPECIFIC VIDEO AND SCULPTURAL INSTALLATION BY HARIS EPAMINONDA

The Museum of Modern Art, 11 West 53 Street, New York, NY 10019, (212) 708-9400, MoMA.org

Interview between curator Roxana Marcoci and artist Haris Epaminonda (October 23, 2011)

RM – Haris, you grew up in Cyprus and then studied at Chelsea College of Art and Design and Kingston University before completing a Master of Arts in 2003 at the Royal College of Art, London. What was the artistic climate then and who would you say was instrumental on your thinking and practice at the time?

HE – I left Cyprus in 1997, right after finishing high school. I was seventeen at the time and my knowledge of contemporary art was incipient. After I moved to London, I became attracted to the city’s museums and film culture. I recall spending hours in the British Museum, The National Gallery, or places like the British Library and the British Film Institute Southbank. I vividly recall an exhibition that we visited at the Royal Academy with Jonathan Miles, a tutor in Critical and Historical Studies at the Royal College of Art, who has played a critical role in my thinking and artistic development. The exhibition was titled The Return of the Buddha. These early Chinese sculptures, discovered in a small town in eastern China, had a beautiful stillness and tranquility and their aura stayed with me ever since.

Can you speak about the project The Infinite Library that you conceived in collaboration with German artist Daniel Gustav Cramer? I am interested in the ideas of archives, cartographies, and atlases at the root of this project, as well as the montage technique involved in splicing books together into new volumes, and in the title, which I believe makes reference to Jorge Luis Borges.

Daniel and I began working on The Infinite Library project in late 2007. We decided to disassemble a few books and reshuffle their individual pages. Once the pages from these various books had been reordered—with glossy and matte surfaces, images of mixed origins and sheets of different sizes—we began experimenting, collecting books and thinking of them as fragments of new volumes. Each page, taken out of its context and placed next to another, formed new associations. The order, rhythm, and logic of the original book was disrupted and reconfigured. The title, The Infinite Library, is indeed inspired by Borges’s short story “The Library of Babel,” in which librarians enter a vast library to search for meaning amongst books that they believe carry all the answers, only to find volumes filled with random content, in every possible variation and sequence.

This disrupting cut-and-paste process recurs not just in The Infinite Library project but also in your series of short videos titled Tarahi, which similarly consist of fragments edited from found videos and films. What does tarahi mean, and what is the underlying narrative, if there is one?

In Greek, tarahi means “turmoil”—specifically, a moment of calm followed by something intense happening. It’s also a state of mind. When I began the Tarahi series in 2007, I was looking at popular Greek movies from the 1960s—romances, thrillers, dramas, comedies—that I had watched earlier, as a child in Cyprus. I realized what an impact they had had on me and decided to rework them. Instead of recreating the original narratives, I would put together short sequences, isolating a small movement or the appearance of a shadow. In this way, I could build up a collage of fragments, selected according to my own emotional responses and arranged according to color or imagery rather than in any sequential story line. As with the

sound composition, the films developed rhythmically, based on changes of mood and atmosphere, building to peaks, creating tension.

The footage that you use in the three-video installation at MoMA, Chronicles (2010), is actually not appropriated but rather shot by yourself over the course of several years. Chronicles eschews narrative in favor of fragmented images that probe the nature of time and assert the permeability of memory. Could you talk about the conception of these works?

Chronicles is an ongoing work that first began to take shape last year in an exhibition at Site Gallery in the UK. It’s a collection of moving images shot with a Super 8 film camera during my research travels. As the title suggests, Chronicles is an ongoing process of documenting and capturing scenes or moments that mark the continuity of time and the layers of history present in places and things. By collecting and juxtaposing these instances and encounters, I’m in some ways trying to build up abstract connections between things as well as observe the passing of time. I study the changes that occur between one event and the next. I see these works semantically, close to how one would form sentences, and attempt to go beyond the concept of mere documents.

Who are the filmmakers that you are drawn to, who inform your practice? And, what is the acoustic link that unites Chronicles in the MoMA installation?

Sergei Paradjanov, Robert Bresson, Yasujiro Ozu, amongst others. The sound is created by Part Wild Horses Mane On Both Sides, an experimental music duo based in Manchester. Their music is mainly based on improvisation, which creates suggestive narratives.

The spatial composition that you conceived at MoMA is titled VOL. VII. How does the video installation interrelate with the sculptural elements —ancient sculptures, earthenware vessels, various plinths, images of archeological finds, and scenes from tourist destinations culled from older books—in the exhibition?

For me the essence lies equally in the distinctive constellations as well as in the formation of one whole visual narrative. The individual films that form Chronicles function as elements, like a vase displayed in a niche, or a thin piece of wood positioned vertically in the centre of the gallery, cutting through space. The conjunction of the films, found images, and objects and their specific locations within the exhibition opens up the possibility of multiple readings, readings that are determined in part by the physical and emotional perspective of the viewer. Perhaps it’s also a question of visual shift, or drift, in the perception of things. Certain motifs are repeated, like an accumulation of gestures that happen to be objects, or things that exist around us in different states of disappearance. For me, these depictions and objects have in the simplicity of their forms a potentially post-apocalyptic impression.

If this installation evokes one emotion, or one level of memory, what would you say it is?

Emotions and memories are always personal. I don’t like to think of the work as generating one emotional state.

THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART PRESENTS SITE-SPECIFIC VIDEO AND SCULPTURAL INSTALLATION BY HARIS EPAMINONDA

First U.S. Solo Exhibition for the Artist

Projects 96: Haris Epaminonda

November 17, 2011–February 20, 2012

Contemporary Galleries, second floor

New York, November 16, 2011—The Museum of Modern Art presents the first solo exhibition in the United States of Berlin-based artist Haris Epaminonda (b. 1980, Nicosia, Cyprus).

Projects 96: Haris Epaminonda is on view November 17, 2011 through February 20, 2012.

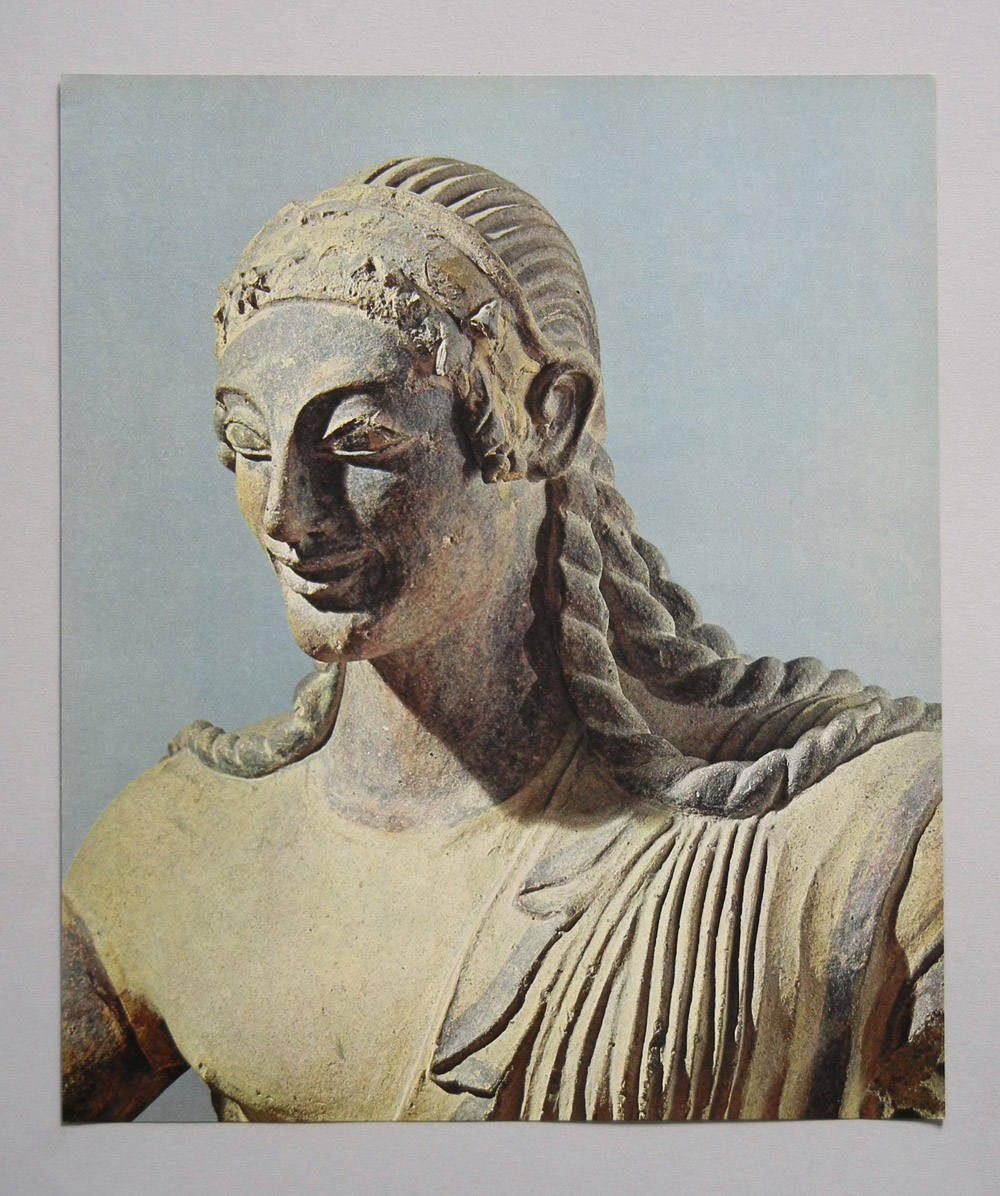

Epaminonda is internationally known for photographic assemblages constructed from found books and magazines of the 1960s, and for video installations in which television footage culled from Greek soap operas that she watched as a child in Cyprus are reshot and re-edited in new sequences, creating a web of elusive associations. In this exhibition, Epaminonda constructs an installation based on connections between a three-channel video projection—part of her work Chronicles (2010)—and a museological-style installation of antique pottery, ritual statuettes, columns, plinths, niches, and pictures culled from magazines and books. Among these books are travelogues about archeological sites that are visually related to each other, yet separated by centuries of history.

―Composed of short Super 8 films that the artist shot over several years, which have been transferred to video, Chronicles eschews narrative in favor of fragmented images that probe the nature of time and assert the permeability of memory,‖ notes Roxana Marcoci, Curator, Department of Photography.

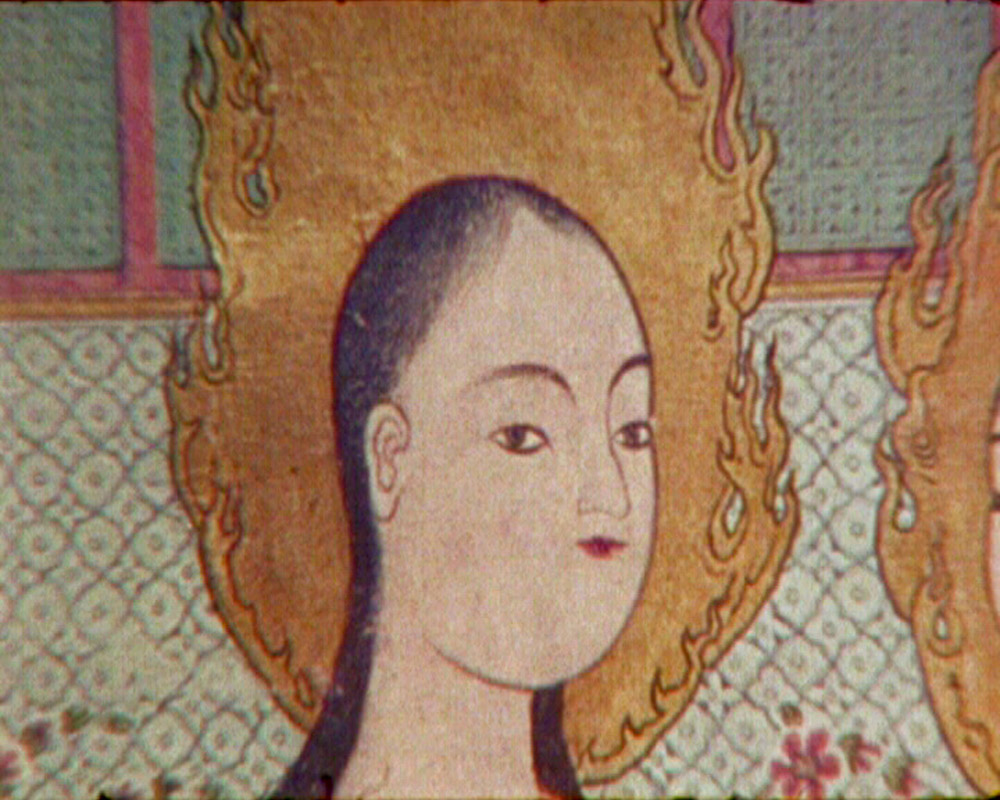

One film shows ancient artifacts from different cultures either isolated against colored backgrounds or in images torn from the pages of an art history book, subtly animated by the slight motion of the handheld camera. In another film, views of the Acropolis evince a twilight state of entropy or decay. The third film simply portrays a pair of superimposed palm trees flickering in the wind in the middle of a barren landscape—remnants of a civilization in decline. The artist enlists a range of techniques, from long takes and unedited footage to fast cuts, narrative rupture, and intensified color. Due to the films being looped and of varying lengths, the image combinations do not repeat. A soundtrack of mixed instrumentation and natural sounds by the band Part Wild Horses Mane On Both Sides provides an acoustic link between the three projections. The moving images, in turn, inform the sculptural installation, creating a three-dimensional audiovisual montage that cuts across temporal and geographic borders.

Projects 96 is organized by Roxana Marcoci, Curator, Department of Photography, The Museum of Modern Art. The Elaine Dannheisser Projects series is coordinated by Kathy Halbreich,

Associate Director, The Museum of Modern Art. This year marks the 40th anniversary of the Projects series, which has played a critical part in the Museum’s contemporary programs.

ABOUT THE ARTIST Haris Epaminonda lives and works in Berlin. She studied at the Chelsea College of Art & Design, at Kingston University, and received an MA at the Royal College of Art in London in 2003. Her work has been shown at solo exhibitions at the Schirn Kunsthalle Frankfurt, Germany (2011); Tate Modern, London (2010); Malmö Konsthall, Malmö (2009); and Künstlerhaus Bethanien, Berlin (2008). Her work has also been shown in group exhibitions at the Sharjah Biennial (2009); Athens Biennale (2009); New Museum, New York (2009); Mori Art Museum, Tokyo (2009); Berlin Biennale (2008); Venice Biennale (2007); and Macao Museum of Art, China (2006).

ABOUT THE CURATOR

Roxana Marcoci, Curator, Department of Photography, joined the Museum in 1999. She has organized many exhibitions at MoMA, including the upcoming Sanja Iveković: Sweet Violence and the recent The Original Copy: Photography of Sculpture, 1839 to Today (2010).

ABOUT THE ELAINE DANNHEISSER PROJECTS SERIES

Marking its 40th year, the Elaine Dannheisser Projects series was created in 1971 as a forum for emerging artists and new art and plays a vital part in MoMA’s contemporary art programs. With exhibitions organized by curators from all of the Museum’s curatorial departments, the series has presented the work of over 200 artists to date. For further information on the series, including a listing of all Projects artists, please visit MoMA.org/projects. To read an interview between curator Roxana Marcoci and artist Haris Epaminonda, please visit the Museum’s website at MoMA.org/harisepaminonda.

SPONSORSHIP

The Elaine Dannheisser Projects Series is made possible in part by The Junior Associates of The Museum of Modern Art.

No Comment