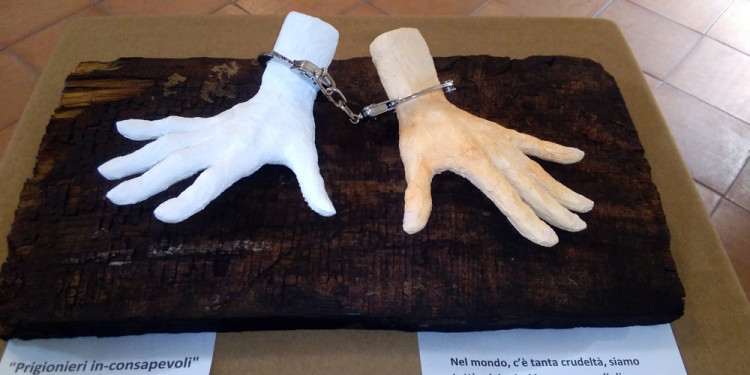

PRIGIONIERI IN-CONSAPEVOLI – MOVIMENTO BRUT – PALAZZO NOVELLI – CARINOLA (CASERTA)

Text by Emiliano D’Angelo

Posizionare il cursore sulle immagini per leggere le didascalie; cliccare sulle immagini per ingrandirle.

Testo di Emiliano D’Angelo

Profeta infallibile per alcuni, per altri “Cassandra rancorosa” e stratega dell’autocelebrazione, Guy Debord aveva visto giusto senz’altro su un punto: la separazione definitiva e dolorosa tra arte e vita reale. La tendenza dell’arte, vale a dire, a degradare rovinosamente a “spettacolo” tra gli spettacoli, generando orpelli da salotto, costosi feticci o gingilli da museo, immagini sublimate dell’accumulazione irresistibile del capitale, giunta a livelli mai vissuti prima nella storia dell’umanità.

La definitività della frattura riposava appunto in questo: che anche le avanguardie, da sempre protese nello sforzo di alimentare una simbiosi incancellabile tra arte e vita, si avviavano ormai a soggiacere alla grande mistificazione della caduta nel regno della merce.

Ma occorre procedere con ordine.

In principio era l’impulso creativo fine a sé stesso, inseparabile dall’essere umano colto nella sua essenza e dal suo (coessenziale) bisogno di emulare e asservire la natura ai propri scopi. Presto l’impulso si caricò di pregnanze magiche e simboliche, passando stabilmente al servizio della collettività. Fu intorno ai simboli e ai simulacri di senso concentrati nei primi manufatti artistici complessi che si coagularono anche le prime comunità arcaiche. Poi si intensificarono gli scambi e nacque la moneta, e il prodotto artistico cominciò a seguire la sorte di tutti i derivati della tèkne immessi nel libero gioco della domanda e dell’offerta di mercato. L’artista dell’antichità era (con l’eccezione di poche realtà isolate, come la Cina confuciana) poco più di un artigiano qualificato. Rifacendosi al Plutarco della “Vita di Pericle”, Gombrich segnala la sostanziale ambiguità mostrata dai Greci, per esempio, nel nutrire “ammirazione per le opere ben fatte, disprezzo per il lavoro manuale dell’artista”.

Da questo pregiudizio ci si comincerà a liberare solo nel Medioevo, con la rivalutazione del lavoro manuale suggerita dalle regole dei primi cenobi cristiani. Riacquistato relativamente tardi anche il diritto di “firma”, gli artisti figurativi conobbero la lunga e controversa stagione in cui le classi al potere erano ancora quelle più colte, e si poteva ambire ad esser venerati alla stregua di vere pop-star ante litteram (si pensi ai casi di Michelangelo, di Raffaello o di Tiziano), ma sempre soggiacendo ai dettami ed alle oscillazioni di gusto di una committenza contrattualmente molto forte, e sotto la sorveglianza più o meno rigida di autorità civili e religiose con potere di interdetto inappellabile.

Com’è noto, il sisma si produsse sul finire del Settecento, e l’epicentro si localizzò in Francia: la grande committenza aristocratica e clericale franò sotto i colpi delle scosse rivoluzionarie. Si definì, pertanto, in pochi anni quell’assetto che ha caratterizzato fino a pochi decenni fa i rapporti fra arte, società e mercato: con il rafforzamento del sistema dei “salons” e delle istituzioni museali, la nascita dei primi fermenti movimentisti e delle gallerie private , l’emergere di avanguardie militanti e agguerrite che attaccavano il sistema rifiutando di produrre opere “appetibili” per i circuiti museali e per la vituperata società borghese. Una èlite di intellettuali, critici e galleristi di ampie vedute provvedeva a legittimare “in tempo reale” il lavoro delle avanguardie, annettendovi di fatto “senso”e “valore”; e il mercato, con un ritardo quasi sistematico che si poteva sedimentare in anni o in decenni, finiva per adeguarsi a tali indicazioni.

L’arte, svincolata dalla pressione immediata delle istanze mercantili, poteva coltivare così l’ambizione (per alcuni, l’illusione) di intrecciarsi con la vita reale condizionandola, di suggerire alternative di senso sociale ed esistenziale, producendo continui scarti in avanti nella direzione di una temporalità verticale e utopistica. All’epoca degli “dei” e dei “giganti” della storia dell’arte aveva fatto seguito un’autentica epopea eroica, solcata più da falangi oplitiche, da regie collettive e manifesti comuni, che non da grandi individualità. L’impulso sociale, prometeico dell’artista primitivo aveva guadagnato nuovo vigore in una prospettiva mutata: laica, immanente, progressiva.

Vi furono figure e collettivi, al culmine di questa epopea, che teorizzarono da prospettive diverse la totale fusione tra arte e vita, come “Fluxus” o la stessa Internazionale Situazionista di Debord, o il movimento della “Happening art” di Allan Kaprow, seguito da numerosi epigoni.

Ma intanto il capitale iniziava a concentrarsi a ritmi vertiginosi, saturando silenziosamente tutti gli interstizi sociali, sgretolando molti dei presidi culturali, ideologici, istituzionali, che potevano fungere ancora da argine alla diffusione del pensiero unico in via di affermazione, supportato dal controllo sempre più pervasivo dei mezzi di comunicazione di massa. Già le transavanguardie degli anni ’80 (pur orientate ad esiti apprezzabili sul piano estetico) sancivano, a ben vedere, la vittoria di una concezione nuova del tempo sociale: non più il tempo dinamico e “irreversibile” della storia, in cui i popoli evoluti erano impegnati in uno sforzo dialettico di superamento continuo delle barriere culturali e delle criticità materiali, ma quello statico ed autoconcluso della postmodernità, della produzione e della crescita fini a se stesse, del consumo autoindotto, dell’intrattenimento non pedagogico ma puramente contemplativo.

In questo contesto stravolto, l’artista è di nuovo, in maniera più sordida del passato, un produttore di merce. L’unica alternativa che gli viene concessa è quella di divenire a sua volta uno stratega della comunicazione; una “vedette”, nel senso debordiano del termine (Cattelan, in Italia, ne è forse l’esempio più eclatante). Non è più il mercato ad inseguire l’arte nelle sue funamboliche evoluzioni stilistiche e concettuali, ma molto più spesso sono gli artisti ad inseguire il mercato, coadiuvati da quei formidabili segugi, da quei cani da riporto che sono diventati i “produttori di valore” di un tempo (critici, galleristi, grandi curatori). Grazie alla loro intercessione sempre più invasiva, l’avanguardia è degradata a pura e semplice accademia, mentre le battiture d’asta delle starlettes del momento arrivano a superare quelle di maestri indiscussi e già storicizzati, generando bolle speculative effimere e pericolosissime.

La verità è che i “produttori di “valore” non sono più in grado di produrre “senso”, avendo smarrito ogni pulsione direzionale; e in qualche caso è persino palese la loro malafede, la loro propensione all’arbitrio assiologico. Più si capillarizza presso le masse l’interesse per l’arte, più, paradossalmente, si attenua la capacità di quest’ultima di far presa e di incidere sulla qualità del vissuto sociale. Si disarticola progressivamente, inoltre, il dialogo serrato e fecondo che il comparto figurativo aveva sempre intrattenuto con la letteratura, la musica ed il pensiero filosofico.

L’arte si riduce sempre più a periferia della moda e dello spettacolo. Quel che è peggio, gli artisti perdono sempre più la capacità di far perno intorno a nuclei concettuali comuni. Il mercato impone competizione, individualità, propensione alla identificabilità di “brand” comunicativi. Se un tempo era servita a suggerire vie di fuga, oggi l’arte corre il rischio di limitarsi a decorare i corridoi di una prigione.

Occorre superare la temporalità statica e asfittica nella quale siamo sommersi, recuperare la socialità dell’arte in una ritrovata dimensione rizomatica e collettiva. Una delle strategie possibili è proprio quella di aggredire la centralità del “brand”, della “firma” d’artista, enfatizzati dal mercato per poter confezionare i suoi feticci. Immaginare una nuova Preistoria, o un nuovo Medioevo, popolato da cenobi di volenterosi operatori della bellezza che mettono la loro manualità, il loro senso critico, la loro capacità immaginativa al servizio di comunità minacciate da impulsi barbarici e regressivi, spesso di natura autodistruttiva.

Il “Manifesto Brut” sembra andare proprio in questa direzione. E l’aver associato il tema della “menzogna” alla collettiva di esordio del movimento, non fa che enfatizzare la forte vocazione sociale di tutta l’iniziativa. Perché la propensione alla menzogna è la patologia suprema del potere contemporaneo. E Bellezza e Menzogna sono due divinità discordi che non potranno mai convivere sotto lo stesso cielo.

Emiliano D’Angelo

Exposition du Manifesto Brut,

www.manifestobrut.org

dans les salles du magnifique Palace Novelli de Carinola.

http://www.carinola.eu/portal/modules.php?name=Content&pa=showpage&pid=26

Du 10 septembre au 18 septembre 2016

Vernissage, le samedi 10 septembre, à partir de 18h00.

Info: + 39 0823734225 GSM. +39 3317308878 – E-mail info@rinotelaro.org

P.za O. Mazza, 81030 Carinola Caserta – Italie

https://www.1fmediaproject.net/2016/09/10/manifesto-brut-palazzo-novelli-carinola-caserta/

No Comment