FUNDACIÓ JOAN MIRÓ – AUTOGESTIÓ – BARCELONA

Parc de Montjuïc, 08038 Barcelona

T +34 934 439 470 – info@fmirobcn.org

curator: Antonio Ortega

The works of the exhibition form a constellation of practices and gestures that constitute a defense of the continued power of the imagination and the creativity.

Stephan Apicella Hitchcock Anne Bean Frank Blum Ben Carey Sico Carlier Mateusz Chorobski Mitya Churikov Layla Dangelo Misha Dare Paul Darius Alan Dunn James Edmonds Noel Ed De Leon Peter Fillingham Thomas Heidtmann Klaas Hübner Brigitte Jurack Elmar Kaiser Daniel Kupferberg Marta Leite Peter Lewis Francesca Manzoni David Medalla Paul Meinel Marita Muukkunen Adam Nankervis Anna Orlowski Alwin Reamillo Denis Salivanov Dirk Sorge St. & St. Ernst Markus Stein Ivor Stodolski Estella Stokol Anja Teske Alma Tischler Wood Valerie Vivancos Deborah Wargon.

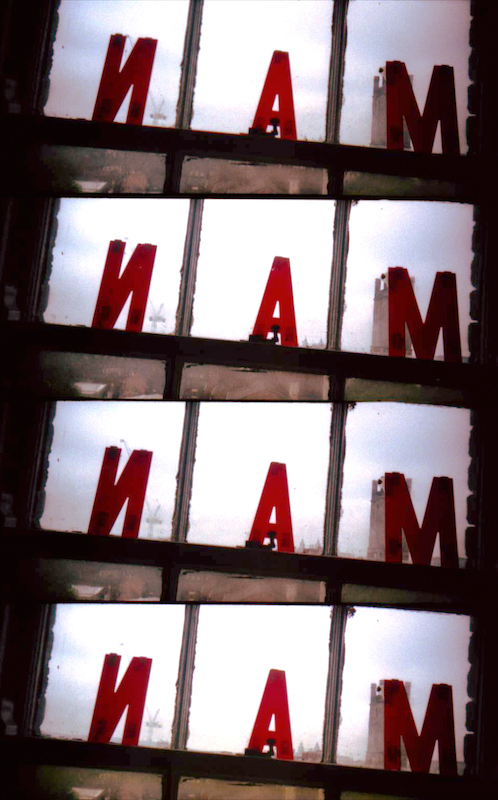

The concept is to replicate the figure of the man in Museum MAN, in sculptural form, like the jigsaw of elements of flotsam jetsam the museum was founded on,as the artists would picture him as whole but by submitting the anatomy of man, or to be more precise, an element of the anatomy of the man. A literal undertaking of a 5′ 10” man laying prostate in space. A homage made collectively, and exhibited at the Miró Foundation Barcelona. As inclusive as this project is, if interested in this more intimate and unique proposal from Museum MAN, a part of the anatomy, clothing, paraphanelia that can be part of this very intimate construction, please contact me, with ideas both of content and material. The base foundation will be clay and wax, but artists are free to choose which part of the man they would want to construct as an independent art work, but within keeping of making up a whole, with the possibility of his atomising into space. An absence of work, an intangible idea, will also be included as in the past, remaining true to the ethos and history of the museum. It remains in the artists´ hands the contributions to be made. One of the cornerstone philosophies of which Museum MAN was constructed.

Adam Nankervis Museum Man

by Guy Brett

By the time I had to leave, my eyes had not finished roaming around, they had only penetrated so far into the dense weave of images, words, masks, momentos, figurines, souvenirs and toys. I had knocked at the door of the staid Georgian house in Liverpool is central district, temporary home of Museum MAN, and of Adam Nankervis, its instigator, who ushered me in. Though part of the Liverpool Biennale 2004, it was an amazing contrast to the big-time fare of painting, sculpture, outdoor commissions and video installations in Tate Liverpool and other venues. Adam Nankervis had brought the contents of his museum over from Berlin and had invited international artists to visit and show their work on the ground floor and eerie cellar. If many of the Biennale works were impressive and aroused various emotions, none surpassed Museum MAN in compelling my curiosity. It is an appropriate word. Most people today trace the origins of the modern museum to the Cabinets of Curiosities assembled in their homes by cultivated grandees of the 17th century (they are the ones we hear about, no doubt those less exalted had their collections too). These cabinets enjoyed a fertile, incongruous mix-up of categories, later distinguished as specialized disciplines: paleontology, natural history, archeology, ethnography, optics, cosmology, art. They were also lived-in museums, and the phenomenon has reappeared in recent times, both as the dens of obsessional collectors, and as the studios of artists. Kurt Schwitters’s Merzbau is an outstanding example. He transformed his house in Hanover into an abstract grotto to contain all the ephemera he collected on his daily rambles. Though he might have wanted to stay for ever in his grotto, he was forced into itinerancy by political events and began a new Merzbau in each principal place of his exile (the poignant remains of the Merzbau he began in a farmer’s barn in the English Lake District are preserved in the Hatton Gallery of the University of Newcastle). Museum MAN, however, is conceived as itinerant. Like Schwitters’s Merzbau, Nankervis’s museum includes the gifts of other artists’s work, or some personal item. Schwitters once purloined a pair of Lazlo Moholy-Nagy is socks after a visit by the Hungarian and incorporated them into his construction. No doubt this personal momento was steered towards abstraction. Abstraction, understood as the play of forms in a state of freedom, released from the old hierarchies and symbolisms, was the great quest of many 20th century artists. Indeed Schwitters wrote of his multivarious salvages: By being balanced against each other, these materials lose their characteristics, their personality poison. They are dematerialised and are only stuff for the painting which is a self-related entity. Nankervis’s museum belongs to an age of vastly expanded production and consumption of imagery: a new media-scape, an acceleration of the process of mediation of the real. Far from losing their personalities his materials take on new personalities as a result of their proximity and interrelationship with one another (this must also be true of Schwitters: his materials do not really lose their personalities; nevertheless the urge towards abstraction does set his collages in their historical moment). Artists have invented museums around specific themes (such as Claes Oldenburg is Raygun collection as the discovery of a mass-cultural icon in the meanest scraps and trash; or Marcel Broodhaers (CHECK SPELLING) Eagle Museum as a critique of power). As well, ordinary people have created live-in, single theme museums. Obsessional collections of Elvis memorabilia or images of dogs are monothematic but plural in terms of object-forms: an Elvis clock, an Elvis hot water bottle, etc. The mythic presence is charmed into every commodity of domestic life. An entrepreneur can profit from the collector is addiction, rare items changing hands for a lot of money, but nobody can exploit the person who collects material according to a philosophy, a poetics, an aesthetic, that only they know. These are the poor man is riches: the right to dream. Accompanying Adam Nankervis to a book-sale in Liverpool, I noticed that he went straight to the 50p rack. He came away with 10 or so books (about 5 pounds worth), some slim, some massive, some plain, some illustrated, related according to some intellectual pursuit the bookseller could not possibly guess. I’m not sure I can either. I can follow certain themes in Museum MAN, for example a certain homoeroticism and interest in masculinities. But other connections are enigmatic and poetic; one can project one is own meaning into them. This museum is a continuum without fixed edges or abode. Two streams seem to converge in it: perceptions of life-currents, which began with the discovery of an abandoned photo-album of an unknown man is life which Nankervis found in a Berlin flat, and the desire to provide a space for artists independent of the art world is system of rewards.

No Comment