MICHAEL NYMAN – KINO SERIE – ANOTHER VACANT SPACE – BERLIN

Michael Nyman

March 2020

to be announced

Kino Serie

another vacant space

Berlin

Nothing I do as a composer is remotely as exciting to me as finding and capturing- and especially editing, my films. I find it is the most creativething that I do….

Michael Nyman

Michael Laurence Nyman, CBE (born 23 March 1944) is an English composer of minimalist music, pianist, librettist and musicologist, known for numerous film scores (many written during his lengthy collaboration with the filmmaker Peter Greenaway), and his multi-platinum soundtrack album to Jane Campion’s The Piano. He has written a number of operas, including The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat; Letters, Riddles and Writs; Noises, Sounds & Sweet Airs; Facing Goya; Man and Boy: Dada; Love Counts; and Sparkie: Cage and Beyond. He has written six concerti, five string quartets, and many other chamber works, many for his Michael Nyman Band. He is also a performing pianist. Nyman prefers to write opera rather than other forms of music.

Machines, Music & Motion: The Cinema of Michael Nyman

Nothing I do as a composer is remotely as exciting to me as finding and capturing- and especially editing, my films. I find it is the most creativething that I do…..I find the ideas that I have just from handling the material goes way beyond anything I do as a composer. I think visual images are more interesting than musical images, even though it will be the musical images that I’ll be remembered for; I’ll never make films that people will say have changed their lives. 1The artist and film-maker Jean Cocteau once described cinema as a “petrified fountain of thought” 2, but this poetic and somewhat disparaging definition could perhaps be equally applied to all photographic media.

The dynamic relationship between the cinema and photography is well documented: the cinema has its roots in the technological developments of an optical stare held for scrutiny and contemplation. At a fundamental level “Cinema” and “Photography” could be understood as two manifestations of the same complex medium- at one end, an instant of time trapped in amber, the other, a limited flow within a pre-defined vessel. 3 Some of the most fascinating examples of the cinematic work of Michael Nyman operate within this fertile territory between the “fountain” of cinema as it performs its shape and the frozen moment of photography. In Striking Poses the film-maker has placed himself at the centre of the film. Nyman is simultaneously presented in multiple roles: as the subject of the camera’s fixed gaze, as the motivation for the continuous activity of the photographer and his assistants, as an artist caught in the act of self-portraiture and as the documenter of the entire operation. In this film there are numerous people operating cameras whilst being photographed, and all of this photographic activity is interrelated and interdependent. The film is focused on the act of being photographed, or perhaps it is the phenomenon of being photographed. It is about the film-maker as the subject of the gaze seeking to acknowledge this position or state and taking control of it by opening up a new space in which the viewer becomes an active participant. If a film of this kind which is at some level a moving photograph, can have a “punctum” (in the sense that it was defined by Roland Barthes in Camera Lucida 4), the punctum is Nyman himself.

In For John, Merce & Tacita From Michael, Nyman has recorded himself exploring a multi-screen video installation by Tacita Dean in which she was directing Merce Cunningham in a performance of John Cage’s 4’33”. Recorded on the morning directly following the announcement of Cunningham’s death, Nyman’s filmic homage includes a moment in Dean’s installation in which Cunningham appears to turn towards Nyman, (and by extension towards the viewer.) .1 “Decisive Moments: A Conversation between Michael Nyman and Chris Meigh-Andrews”, Michael Nyman, Images Were Introduced, Venaria Reale, Fondazione Elisabetta Sgarbi, Turin, June 2017, p. 33.2 Jean Cocteau, Esquire Magazine, Feb 1961, p. 25.3 Even the “real time” flow of electronic image data from a surveillance camera or web cam has an end point, (pre)determined by the limits of its operational capacity; it will at some stage be switched off, disconnected or simply cease to function, and the images will stop flowing.

4 Roland Barthes, Camera Lucia: Reflections on Photography, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, Paris, 1981.

As the title of this film suggests, and as Nyman himself has pointed out, there are many layers to this work: “A lot of cultural identities were being referred to at that (as always) haphazard moment of filming that film.” 5 Not only does the film reference the complex relationship between the dancer Merce Cunningham and the composer John Cage, but it also connects and resonates with Nyman’s own creative trajectory, both as a composer and as a writer and critic. Nyman’s insightful and influential book Experimental Music: Cage and Beyond (1974) takes Cage’s watershed 1952 composition as its central point of reference in order to explore the relationships between what is usually considered the essential unity between the acts of composing, performing and listening to music. In his book Nyman identified 4’33” as central to his definition of experimental music, explaining that: “it is the most empty of its kind and therefore for my purposes the most full of possibilities”. 6 Cage’s ideas on the distinctions between the activities of musical composition, realisation and audition also shed light on Nyman’s approach to his film-making, particularly the way in which the distinctive phases of the activity are identified and developed. He encounters a subject, identifies it as “recordable”, then records, transcribes and annotates it, finally putting it into context. Via this approach we are made aware of the distinct phases of this process and are thus encouraged as viewers to become actively engaged with the work.

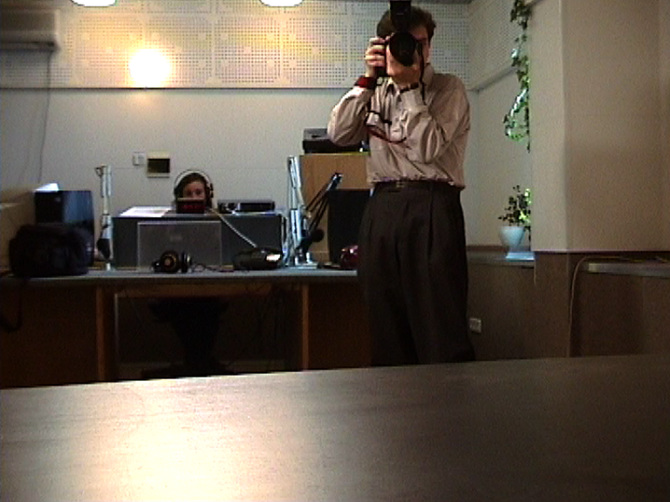

In Moscow 11:19:31 Nyman records the people and activities around him during an interview at a Moscow radio station. Bored with the proceedings (perhaps having to reply to questions which were all too familiar), he took out his camera and began recording. The resultant film allows us to become even more aware of Nyman himself as the focus of attention, his lens capturing the attentive gaze of all the participants. Additionally, the work has fostered an innovative experiment with the soundtrack. Working with this material during the post-production phase, Nyman and his editor have cut out his answers, using the “ummms” with which he begins each response as a cue for the music which replaces his speech. Exploring the potential of this new device for triggering the non-diegetic music track has led to the development of an experiment in which the same film material has five different styles of musical soundtrack. Nyman is fascinated with the relationship between the photographic image (composition, framing, and subject) and the foregrounding of various kinds of movement within his films, developing an approach which could be characterized as “Expanded Photography”. These works extend the photographic moment into the subject of the film. This approach to film making has in part been facilitated by the ease with which it is now technically possible to switch between making still images or recording movement with a single compact camera. With his digital camera, Nyman is able to engage with and record the circumstances of his observation.

In The Art of the Fugue he both records and participates in an impromptu photo session he came across in Plaza Luis Cabera in Mexico City. For Nyman the initial attraction is the way in which the accidental and the co-incidental are conflated. It is the observation of activities and actions that I don’t participate in and that nobody controls. If we take the girls on the square in “The Art of the Fugue” as a kind of model, they moved around in relation to each other and to the photographers, and the entire mis-en-scene was set up for me- but not set up for me, because nobody knew or had any consciousness of my engagement. What was also kind of interesting is that I’m filming the filming.

7 In The Art of the Fugue, as Nyman’s camera records the process of making the film, artist and camera move freely around around the pro-filmic event- engaging and participating in the event as it occurs, simultaneously capturing and creating movement. This “filming of the filming” is a device that continually occurs within Nyman’s film work. He is continuously seeking and open to what he considers to be a Fluxus event- a situation in which a filmic opportunity literally unfolds in front of him.“….there’s this whole issue of the fact that the entire thing is there, perhaps people see it, or perhaps they don’t notice it. I not only see it, but I also decide to capture it”. 8 In a number of the films, such as Tieman, Metal Bangers and Moscow 11:19:31, there are gestures and looks from people within the film who have become conscious of the camera. The inclusion of this material enables the viewer to pick up on the structure of the film itself. In Refusal, Nyman follows the protagonist, who is oblivious of the camera, along the street with his sacks of rubbish. As viewers we become conscious (and complicit) with the film-maker’s thought process. In the film, the camera turns back to look at the sacks left on the street, uncertain as to what is happening, and what will occur next. The “purpose” of the film is allowed to unfold in front of the viewer, just as the incident had unfolded in front of Nyman at the time of filming. The film becomes a bridge between the past, when the recording was made and the present moment at which we are experiencing the film. Some films are centred on the photographic image itself.

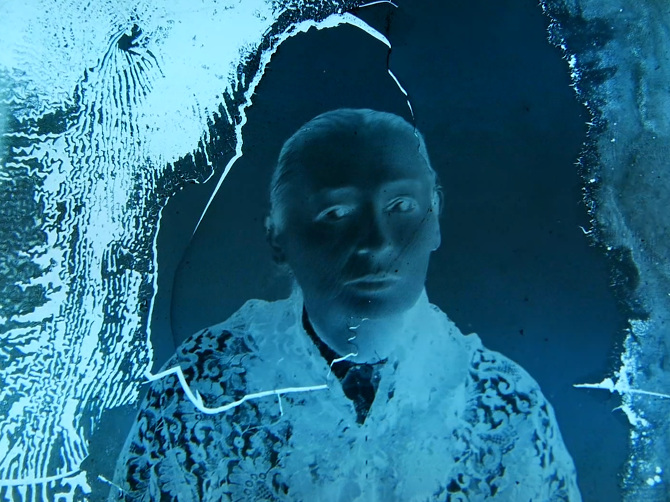

Empressa Cines Merida presents the viewer with an archive of fading glass negatives and fragments of documentary film footage, many of which are in an advanced state of decomposition, the emulsions cracked and flaking, obscuring faces and expressions. These once treasured images are disappearing, just as the knowledge of who these people were and what they were doing has been lost or forgotten. The film temporarily re-animates them, their faces brought to light briefly in front of Nyman’s camera, only to be returned to the dark vaults of the archive. The film is a powerful comment on the effects of time. Although these people are rendered nameless, their faces from another time and place, their expressions, clothing and appearance generalised, we are touched by their shared humanity and are reminded of our own potential future as anonymous faded images in someone else’s present. The process of capturing phenomena as a cumulative, serial activity is important to Nyman, and there is an entire category of films in his oeuvre that have been developed out of this cinematic collecting activity. Slow Walkers is a prime example of this approach. The work was produced once Nyman realised that he had enough material to make the film, having made recordings of individuals walking slowly “for whatever reason and in whatever location” over a number of years. 9 This approach to collecting video material that begins as a purely visual, serial activity, has in this case, resulted in a film infused with pathos, but never sentimental. Nyman defines this approach as “list-making”, citing his shared affinity with Peter Greenaway, a film director with whom he has collaborated with on numerous occasions.

One thing that (Peter) Greenaway and I had in common was a sense of making lists; To be serial in the best sense of the term and to make categories-even before I started on this pursuit of Vertov. Every time I saw somebody walking slowly, for whatever reason and in whatever location, I would film them. When we did our first edit of this work, I realised I had enough material to make the film. Basically it was purely visual- there was no sense of the sadness of it all, it was simply slowness as a phenomenon. 10When asked about his film-making activities, Nyman characterises himself as a “street video artist”. 11 This characteristically self-deprecating description is limiting in that it describes only one aspect of his increasingly complex oeuvre of moving image and sound. The visual content of films such as A Zoor Point, Ice Tango,The Whole Weld and No Bullmay have had their origins in Nyman’s observational skills and fascination for the detail and idiosyncracies of human activity, but via the process of image post-production and editing, blended with music and sound, they emerge as an articulation of colour, form, choreographed movement and interaction. Although this observational approach is a significant characteristic of Nyman’s moving image work, the films can take other forms too. For example, the Witness series pays tribute to forgotten victims in the Nazi concentration camps (Witness I and II), the 2014 Iguala mass kidnapping in Guerro, Mexico (Witness 43) and the Hillsborough stadium deaths in Sheffield, England (Witness 96). This series of four short films present an alternative to Nyman as “street video artist” and this approach has emerged in a more substantial form in his recent feature-length film War Work: 8 Songs and Film.

Nyman’s films are the result of a close and productive collaboration with his editor Max Pugh, an accomplished film-maker in his own right. 12 This partnership, which began in 2007 with a survey of hundreds of hours of video and film material that Nyman had amassed over many years, has evolved into a creative alliance based on mutual understanding and trust. Although they are both busy on their own individual projects, Nyman and Pugh strive to maintain a schedule of regular meetings- getting together for at least a couple of days every month to exchange ideas and discuss and view new visual material. There is also the inevitable constant flow of e-mails in which creative ideas and approaches are discussed and reviewed. The editing techniques in Nyman’s work can vary from the deliberately minimal, to the highly manipulated. In works such as Love Train, Tateman and Tieman, for example, Nyman and Pugh have preferred to simply “top and tail” a sequence to produce self-contained and concise filmic essays. Pugh has explained that during the editing process he looks for the “Nymanesque” qualities within the material- the “humorous, sometimes mocking take on human behaviour”, and Nyman’s “eye for patterns and repetition- both mechanical or human.” 13 In contrast to this minimal editorial intervention, other films are the result of considerable digital post production work- multiple superimpositions and image transitions as well as rostrum camera techniques applied to still images.

This complex post-production is very evident in films such as the Witness series and are a feature of the large-scale projects War Work and Nyman With a Movie Camera. Nyman With a Movie Camera is a continuously evolving 12 screen projection installation. The original idea was prompted from a suggestion from Pugh to develop an installation featuring images and sequences from Nyman’s filmic work edited to his soundtrack for Dziga Vertov’s original ground-breaking silent film, commissioned in 2002 by the BFI. Pugh explains that their editing process has stimulated the shooting of a significant amount of original additional visual material, Nyman With a Movie Camera was developed via the re-interpretation “either literally and metaphorically” of each shot in the original film. Both editor and composer have developed a deep knowledge of the Vertov film, having cut the original into over 1500 individual shots. This resultant deep familiarity with Vertov’s film and its affinity with “ordinary life” has influenced and inspired Nyman, who sees “Vertov all around him” wherever and whenever he travels.

Although the potential number of screens for the installation is infinite, Nyman and Pugh decided they would limit the total number to twelve; eleven “remakes” and one devoted to presenting Vertov’s film in its original unedited form, inspired and guided by Vertov’s own description in his 1923 essay Film Directors: A Revolution. … I am the cinema-eye. I am a constructor. I have set you down, you who have today been created by me, in a most amazing room, which did not exist up to this moment, also created by me. In this room are 12 walls filmed by me in various parts of the world. Putting together the shots of the walls and other details I was able to arrange them in an order which pleases you, and which will correctly construct by intervals the cinema-phrase, which is in fact a room….15 The multi-screen projected installation format of Nyman With a Movie Camera allows the viewer freedom to encounter and select the images and sequences in a complex (and virtually endless) variety of ways, extending the editing process beyond the post-production phase into the exhibition venue.

Nyman’s strategy of continuously re-editing and replacing sequences is enhanced by the potential for audience interaction and engagement. Vertov’s “amazing room” has been re-created, each luminous and carefully choreographed wall can be viewed, revisited, re-viewed and re-ordered. Naturally, Nyman’s own music is a defining characteristic in nearly all of the films, although he has not made his films in response to any of his musical compositions and has never written a musical soundtrack for any of his films, but rather selects pre-existing music tracks from his large personal archive. 16 There are however, occasions in which Nyman has reworked his music as a direct response to a specific requirement. In El Ritmo del Sismo for example, Nyman developed a new version of his saxophone quartet Song for Tony, editing the film’s four locations to a soundtrack made up of different versions and different recordings of the same piece of music. This kind of innovation has been prompted by the requirements of the film and has presented Nyman with new creative approaches to his film sound track work:I would never have done that just sitting down and asking “how can I make a soundtrack?” And no film-maker would have encouraged me to do it. So there’s that sense in which the film-making involves me as a composer and a “re-composer”. 17 Although most of the films combine their imagery with Nyman’s own musical compositions, some of the film soundtracks have been developed from alternative approaches.

Guns n’ Dolls overlays the mechanistic repetitive sound of talking dolls recorded in a toy shop to build up layers of sound; Pretty Talk features a looped recording of a woman’s voice endlessly attempting to teach a parrot to speak whilst the multi-screen film Tea Factorymakes use of the ambient sound of the factory itself. Metal Bangers, filmed in the Iranian city of Isfahan, combines the ambient sounds of hammering metal workers with the sound of chiming bells recorded at St Florian’s Cathedral, near Linz. Nyman is challenged and excited by the realisation that he can be more inventive when working on a film sound track than he was able to be as a sound track composer. This cross-fertilization of sensibilities from one medium to the other is possible because of Nyman’s deep understanding of how musical structures can be directly applicable (and transferrable) to particular filmic structures. The duration of the films is often determined by the choice of music. According to Nyman’s editor Max Pugh, the choice of music can sometimes be random, an approach which he points out is much more common in film-making than appreciated. Pugh also notes that it can produce unpredictable and unexpected surprises. However, there are also examples of films in which very conscious choices were made such as The History of Cinema Pt 67, where the beach and cinematic connotations prompted Nyman and Pugh to opt for music composed for The Piano. 18 War Work: 8 Songs and Film, commissioned by the War on Screen International Film Festival to commemorate the 100th anniversary of the First World War, is an ambitious and complex piece, and according to Nyman his greatest work to date. 19 It is comprised of a feature-length film and a cycle of 8 songs, combining chansons vielles with words by European poets and archival documentary material filmed during the 1914-1918 conflict. Much of the visual material of War Work was drawn from the military archive in Paris using film footage that had not been previously shown. According to Nyman this was not simply due to the disturbing nature of the footage, but also because it was relatively inexpensive to acquire. Significantly, Nyman found much of this visual material reminiscent of the silent films that he had previously scored, including Sergi Eisenstein’s Battleship Potemkin (1925), Paul Strand’s Manhatta (1921) and Jean Vigo’s A Propos de Nice (1930). However it was Nyman’s work with three particular films by Dziga Vertov; Man With A Movie Camera (1929), The Eleventh Year (1928), and A Sixth Part of the World (1926) ,as well ashis deep familiarity and knowledge of the structure and content of these films that further enhanced his research into the musicality of Vertov’s films. For example, discussing the CD Vertov Sounds on his web site, Nyman quotes from a text by the Soviet film critic Izmail Urazov in Lines of Resistance: Dziga Vertov and the Twenties: 20 That is the cause of the emotion which the film arouses.

You cannot relate it; there is no plot, no intensification of the action, but there is an intensification of emotion. Like in music. That is where the emotion comes from. Vertov leads the ʻmelodyʼ, returning to it, playing with dissonances, using the exoticism of the polar snows and the burning hot sands, almost like something beyond sense, almost like a composer using the texture of the sounds. 21 A number of key visual passages in War Work relate to Nyman’s fascination with the “Body-as-Machine”, a theme which also features in his operas The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat, Facing Goya and Love Counts as well as in the song cycles Body Parts Songs and I sonetti lussuriosi. There isa complex cross-fertilisation of themes and ideas connecting music, poetry, visual art and film at the core of War Work, and this approach has much in common with Dada, a movement with which Nyman himself has considerable affinity. To a large extent, Dada developed in Europe and the United States as a direct reaction to the horrors, destruction and waste of World War I. Dada artists were united in viewing the conflict as a direct result of the failure of modern capitalism in the West. War Work includes what Nyman has described as “hesitant references” to Dada, as well as to works by the painters David Bomberg, Mark Gertler and Issac Rosenberg. 22 Nyman’s relationship to Dada as a composer is complex, and has been discussed in Pwyll ap Sion’s book The Music of Michael Nyman in some detail. 23 Nyman’s approach to musical composition via Dada has clearly been extended and deepened to integrate his work with the moving image, and there are some useful parallels to be drawn between the two. Nyman’s film-making employs similar methodologies and techniques which incorporate “whole networks of intertextual associations…on both implicit and explicit levels”. 24 In this respect War Work is an example of Nyman’s ability to integrate the musical and the visual to produce an evocative and powerful work which has justifiably received considerable critical acclaim. 25War Work represents a further maturing of Nyman’s film-making; an integration of ideas, techniques and working methods drawn from both his musical composition and his previous moving image work. The film resonates with his work and thinking as a composer of film sound tracks and opera, and his deep knowledge and understanding of avant-garde. 20 Yuri Tsivan, ed, Lines of Resistance: Dziga Vertov and the Twenties, Indiana University Press, 2005. 21 http://www.michaelnyman.com/vertov-sounds/, consulted 24/07/1722 Nyman in conversation with Chris Meigh-Andrews, p 41. 23 Pwyll ap Siôn, The Music of Michael Nyman: Texts, Contexts and Intertexts, Ashgate Publishing ltd, Farnham, 2016, 24 Ibid, p 9. 25 Two examples: “War Work feels like an elegy to a lost generation, one channelled through three centuries of musical history; it’s an eloquent and sometimes strikingly beautiful piece”. Andrew Clements, The Guardian, 09/12/2015. “Most of the pieces written to mark the centenary of the War have set out to wring our hearts, rather than make us think. Nyman’s does both, magnificently”.

Ivan Hewitt, Daily Telegraph, 11/12/2015

Music and film. Taken together, Michael Nyman’s films already constitute a substantial body of work, and it is clear from the evidence of War Work: 8 Songs and Film that the potential for further integration between Nyman’s music and his moving image work will create an even more significant and lasting achievement.

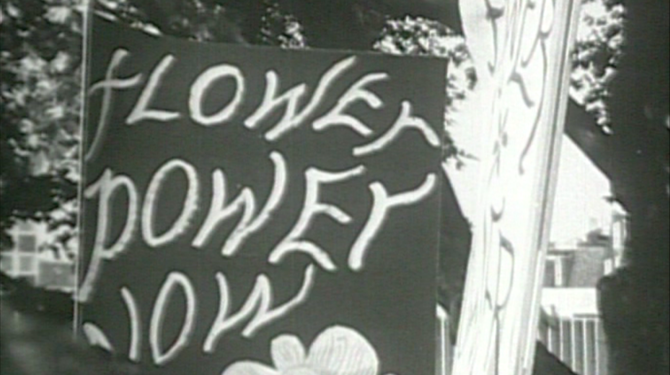

LOVELOVELOVE

Michael Nyman 1968

facillitated by Adam Nankervis

another vacant space

www.anothervacantspace.com

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/another_vacant_space/

https://www.facebook.com/anothervacantspace/

Position the cursor on the images to view captions, click on images to enlarge them.

No Comment